As we enter Holy Week the thoughts and prayers of Christians will centre around the events which lead up to the Passion and Death of Jesus. These are described in the Four Gospels by the Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and Johh.

The vast majority of Catholics have never had the opportunity to study the Passion Narratives contained in the Gospels, so I am attempting to provide some basic teachings about them.

At the outset, I wish to acknowledge my debt to the late Fr Raymond E. Brown SS, whose Essays on the Four Gospel Passion Narratives are contained in a small booklet published in 1986, A Crucified Christ in Holy Week.

I shall try to present a condensed version of the 80-page booklet under the following Headings.

A: The Three Stages in the Formation of the New Testament.

B: Who and What are Evangelists?

C: How were the Gospels formed?

D: The Passion of Jesus.

E: Eucharist- origin of the earliest Passion Narratives.

F: The Passion Narrative is a Document about Faith

G: The Passion Narratives are ‘historical’.

H: The Old Testament – a vital source of material for Passion Narratives.

I: The Passion Narratives have their own perspective.

J: How were the Passion Narratives formed?

K: Participation of the Audience is invited.

L: Passion Narratives are coloured by real life situations.

M: Factors surrounding the Death of Jesus.

N: From Gethsemane to the Tomb.

O: Diverse Portrayals of the Crucified Jesus

P: Which Gospel is the most accurate/trustworthy?

It is my hope that this Presentation will help you as you walk with Jesus on his journey to Calvary and also with those who now suffer from the ravages of war.

A: The Formation of the New Testament

But before launching directly into the topic of The Passion Narratives, I am going to prepare the ground by looking very briefly the Origin of the New Testament and then how the Gospels came about.

I want to introduce you to the Three Stages of the Formation of the New Testament

Jesus of Nazareth 1 – 30 AD

The First Christian Communities 30 – 70 AD

The Editing of The Writings 70 – 100 AD

There are 27 books in the New Testament.

The first 4 books are Gospels; the remaining 23 are made up of Letters / Writings mostly by St Paul and some other authors.

Most Scripture Scholars hold the view that the Gospels:

– were written between the year 65 – 95 AD

– first one written was Mark;

– last one – John – about the year 95.

– Matthew and Luke were written sometime in between.

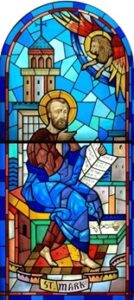

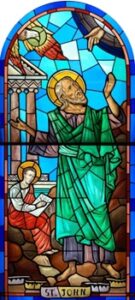

B. Evangelists

The word Gospel comes from the word “Godspel”, an old English word, meaning ‘Good News’. The corresponding word in Greek is ‘Evangelion’. It is from this Greek word that we get the English word, Evangelist, that is, someone who wrote a Gospel. Who these people were we cannot say for certain. It is generally accepted that none of them

– were apostles.

– actually walked around with Jesus during his three? years ministry.

– were present at his death.

– actually saw Jesus being raised from the dead.

Yet, they stated in their writings – the Gospels – that they had an intimate knowledge of Jesus and that they believed in him. For them, Jesus was the Christ, the Son of God.

We know that they compiled their Gospels from selected materials – sayings of Jesus, stories about Jesus and about the apostles. They had heard these from those people who were themselves eyewitnesses… people who had seen and heard what Jesus had done and said during his earthly ministry in Judea and Galilee.

There is general agreement among Scripture Scholars that even before Mark wrote his gospel there were some existing accounts of various aspects of the passion. Each of the Evangelists put his own stamp on them… and edited them to his own purposes.

C. How Were Gospels Formed?

C. How Were Gospels Formed?

Most Scripture scholars claim that the gospel tradition was formed “backwards’, starting from Jesus’ resurrection and working back towards his birth.

The apostles and disciples who preached about Jesus initially gave a lot of emphasis to the crucifixion and resurrection. In the Acts of the Apostles, preachers, notably Peter, said on several occasions: “You killed Jesus by hanging or crucifying him, but God raised him up.” Then, as Christians reflected on the earlier life of the Crucified One, accounts of Jesus’ public ministry emerged, and eventually accounts of his birth. [And as a matter of interest, it is only Matthew and Luke who tell these stories. Mark and John have nothing to say on this matter.]

D. The PASSION of Christ

When we talk of a Passion Narrative, we refer to the story of how Jesus suffered and died. The Passion story occupies a very important place in all four gospels. In MARK this is very striking; his treatment of the Passion takes up 20% of his gospel.

E. Eucharist – the Origin of the earliest Passion Narrative

E. Eucharist – the Origin of the earliest Passion Narrative

The Passion Narratives grew out of real-life situations. Within a few years following the death and resurrection of Jesus, the first Christian communities began to celebrate the Eucharist. St. Paul, writing about the year 53 AD describes what the communities were doing when they met together for worship.

In Chapter 11 of his 1st Letter to the Christian community in Corinth, Paul states:

“For I received from the Lord the teaching that I passed on to you;

that the Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed,

took a piece of bread, gave thanks to God, broke it, and said,

‘This is my body, which is for you. Do this in memory of me.’”

“In the same way, after the supper he took the cup and said,

‘This cup is God’s new covenant, sealed with my blood.

Whenever you drink it, do so in memory of me’.”

When they met, they would have a meal together. This was their way of remembering him. And St Paul continues,

“Every time you eat this bread and drink from this cup

you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.”

Scholars have little doubt that the earliest Passion Narrative took shape in the eucharistic celebrations of the early Christian communities.

When they gathered, they would recall the night of the betrayal, the events of the crucifixion, and the happenings at the tomb. In our gospels the account of the Last Supper became part of the introduction to the Passion Narrative proper. [Those of you have been taking part in the New Stations of the Cross will have noticed that the 1st station is no longer ‘Jesus is condemned to Death’ but ‘The Last Supper.]

F. Passion Narrative – a Confessional Document

The most important element that influenced the growth and character of the Passion Narrative was the confession of faith of the Christian church. The suffering Jesus was proclaimed –

– the Son of man to whom is given all power in heaven and on earth;

– by his death and resurrection he redeemed humankind and gained a new people;

– one day he will come to judge the living and the dead.

These narratives should be read in the spirit in which they were written – as confessional documents which are meant to elicit the response of faith rather than to inform us about the minute details of the passion and death of Jesus.

G. The Passion Narratives are ‘historical’

G. The Passion Narratives are ‘historical’

There is no doubt that Jesus of Nazareth existed; and that at the end of his life he appeared before Pilate and died by crucifixion. All this is history. But here in the passion stories, as elsewhere in the gospels, we are given, combined in a single picture, both the historical Jesus and the Church’s understanding and proclamation of Jesus as they developed in the early years after Jesus’ death.

I’m sure you have all seen a photo in which there were 2 images, one superimposed upon the other. This will help you appreciate what I mean when I say that that it is very difficult to make clear distinctions between what is history and what is interpretation. In fact, there is no such thing as ‘pure history.’ e.g. a car accident; the accounts of war in Iraq. Depends on what the eyewitness saw and what the Reporter wrote about an incident.

The PASSION NARRATIVE is an interpreted history of the passion. In the gospels we encounter the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith.

H. Old Testament – a vital source of material for Passion Narratives

H. Old Testament – a vital source of material for Passion Narratives

Another element that shaped the earliest Passion Narrative is the constant reference to the Old Testament (OT). The early Christians were intent upon showing that God’s will, as expressed in the scriptures, was fulfilled in Christ.

Indeed, the use of allusions from the OT colours the factual account, showing that the evangelists were not writing mere history. But it is also clear that what was interpreted had a basis in fact. It was historically true.

Those of you who are familiar with the scripture passages selected by the Church for the Masses of Holy Week may be aware that the 1st Readings on Holy Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and especially on Good Friday are all taken from Isaiah. They are called the Songs of the Suffering Servant of God. Even though they were written 100s of years before the event, one can easily see how the first Christians interpreted them as referring to Jesus.

Isaiah has the Suffering Servant say:

“For my part, I made no resistance, neither did I turn away.

I bared my back to those who beat me.

I did not stop them when they insulted me, when they spat in my face.

[Isaiah 50:5-6 on Holy Wednesday]

“As the crowds were appalled on seeing him –

so disfigured did he look that he seemed no longer human –

without beauty, without majesty we saw him,

a thing despised and rejected by others;

a man of sorrows and familiar with suffering.”

[Isaiah 52:14; 53:2,3 on Good Friday]

Why did Jesus have to go through all this? It was for us!

“Ours were the sufferings he bore, ours the sorrows he carried.

He was pierced through for our transgressions, crushed for our sins.

On him was the punishment that made us whole,

and by his bruises we are healed.

The Lord has laid on him the iniquity of all.

He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he did not open his mouth.

He poured out himself to death,

and was numbered with the transgressors.

[ Isaiah 53: 4 -12 on Good Friday]

I. The Passion Narratives have their own perspective

I. The Passion Narratives have their own perspective

In fulfilling the scriptures, the Passion Narratives reveal the person of Jesus and the final days of his work. The Old Testament provides a backdrop for this. The following passages bear this out.

That Jesus would be the Messiah(Ps110).

The references to the coming of the Son of Man in the Book of Daniel.

The suffering of the Just One (Pss 22 and 69).

By assuming the role of the suffering servant of God, Jesus enters into his glory, not as an earthy Messiah, but as Son of God.

None of the evangelists emphasize the physical sufferings of Jesus. (They would not be too happy with the way that some communities in the Philippines highlight the flagellation and the re-enactment of the crucifixion).

The early Christian communities and the evangelists did not intend the Passion Narratives to be an accurate, historical reconstruction of what actually happened but rather faith-interpretations of the passion developed after, and in the light of, Easter.

J. Passion Narratives – How Were They Formed?

J. Passion Narratives – How Were They Formed?

The shaping of a basic account of the crucifixion would have been facilitated by the necessary order of the events. Arrest had to precede the trial and execution. So, in all our 4 Gospels we have a narrative with a developing plot, tracing the actions and reactions not only of Jesus but also of a cast of surrounding characters, such as Peter, Judas, and Pilate. The impact of Jesus’ fate on various people is vividly illustrated, and the drama of the tragedy is heightened by contrasting figures.

Alongside the innocent Jesus who is condemned to death is Barabbas – a revolutionary who is freed even though guilty of a political charge similar to the one levied against Jesus. Alongside the scoffing Jewish authorities is a high ranking Roman solider who recognizes him as Son of God. Each passion narrative constitutes a simple dramatic play.

Indeed, John’s account of the trial of Jesus before Pilate comes close to supplying stage-directions, with the chief priests and “the Jews” carefully stationed outside Pilate’s palace while Jesus was inside alone with him. The shuttling of Pilate back and forth between the two sides dramatizes a man who is trying to find a middle position. He doesn’t want to condemn; he doesn’t want to acquit. Yet the tables are turned, and Pilate, not Jesus, is the one who is really on trial, caught between light and darkness, truth and falsehood. Jesus challenges him to hear the truth (John 19:37). When Pilate replies, “What is truth”? John is warning the reader that no one can avoid judgment when he or she stands before Jesus.

The different character types in the passion drama serve a purpose. We, the readers, or hearers, are meant to participate by asking ourselves how we would have stood in relation to the trial and crucifixion of Jesus. So, whenever you read or listen you should be asking yourself the question, “With which character in the narrative would I identify myself?”

You will have noticed that the 6th Sunday of Lent is known by two names… because it has two Gospels. The 1st gospel is about Palms; the 2nd gospel is about the Passion of Jesus – Palm Sunday of the Lord’s Passion.

While listening to the 1st Gospel or walking in the procession I can easily identify myself with the crowd who hailed Jesus as king. But then as I listen to the unfolding of the story of the Passion, I might have been among the disciples who fled from danger, abandoning him. Or at moments in my life have I played the role of Peter, denying him… or even the role of Judas, betraying him?

Have I not found myself like the Pilate in John’s gospel trying to avoid a decision between good and evil? Or like the Pilate in Matthew, have made a bad decision and then washed my hands so that the record could show that I was in fact blameless?

Or, most likely of all, might I not have stood among the religious leaders who condemned Jesus? If this possibility seems remote, it is because many have not really understood the motives of those who opposed Jesus. E.g. Mark’s account of the trial of Jesus conducted by the Chief Priests and the Jewish Sanhedrin (Cabinet / Council) portrays dishonest judges with minds already made up, even to the point of seeking false witnesses against Jesus.

L. Passion Narratives are coloured by Real Life situations

L. Passion Narratives are coloured by Real Life situations

This brings us to one of the many things we must remember when we read the Gospels. The memory of what happened in Jesus’ lifetime was affected by what was happening in the local Christian communities around the time the Gospels were being written.

One factor that coloured the writing was the fact that the Gospels were written at a time when the world was governed by Roman law. Tacitus, a Roman historian, who was not a Christian and had no love for Christians, describes Jesus as a criminal put to death by Pontius Pilate, the procurator of Judea. Christians could offset this negative description by using Pilate as a spokesman for defending the innocence of Jesus.

If one moves consecutively through the Gospels account of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John, Pilate is portrayed ever more insistently as a fair judge who recognized that Jesus was not involved in political issues. Hearers of the Gospel in the areas around Rome had the assurance that Jesus was not a criminal.

M. Factors in the Death of Jesus

M. Factors in the Death of Jesus

Another factor which coloured the Gospel accounts was the bitter relationship between the Christians who had been converted from the Jewish Religion and those who remained as practicing Jews. Matthew would have us understand that all the Jewish authorities were opposed to Jesus. Yes, there were some who were worried about their own positions. You remember that the family of Annas and Caiaphas were deeply involved in swaying the Sanhedrin to vote for the execution of Jesus.

There would certainly be several leaders who were sincere in their belief that they were serving God by getting rid of a troublemaker like Jesus. In their view, Jesus was a false prophet misleading the people by his attitudes to ‘work on the Sabbath’ and consorting with sinners! According to the Law of Deuteronomy the false prophet had to be put to death lest he seduce the Chosen people from the true God.

If Jesus was treated harshly by the religious minded people of his time who were Jews, it is quite likely that he would be treated harshly by religious people of our time. And this includes Christians. It is not Jewish background but a religious mentality that is the basic component in the reaction to Jesus.

The exact involvement of the Jewish authorities in the death of Jesus is a complicated issue so we cannot go into it here. Suffice it to say that depending on which author you read, you will put blame on or take away blame from the authorities for what happened to Jesus. Pilate was acting on behalf of Rome. His boss was Caesar; on the local scene you had Pharisees, the Sanhedrin, and the high priestly families. Religious people of all times have accomplished what they want to do through the secular authorities who, of course, are acting for their own purposes.

Matthew and John generalise the Jews with hostility. Not only is the Jewish leadership blamed for Jesus’ execution but the general population. Some famous Christian theologians (Augustine, Thomas Aquinas and Martin Luther) have made statements about the Christian duty to hate or even punish the Jews because they killed the Lord.

[Those of you who have been churchgoers before the Second Vatican Council would have heard in Latin a prayer on Good Friday. In the Section called The Solemn Intercessions the Church prayed for ‘the perfidious Jews’! In 1957, this description was removed. The current text reads like this: “Let us pray for the Jewish people to whom the Lord our God spoke first……”

N. Passion Narrative – Gethsemane to Burial

N. Passion Narrative – Gethsemane to Burial

What does a Passion Narrative consist of?

Does it begin with the Last Supper, and does it include the women’s visit to the empty tomb? Certainly, Luke thought of the Last Supper, the arrest, the passion and death, the burial, and the visit to the tomb as one unit.

For practical reasons, what we call the Passion narratives deal with everything that happened to Jesus from Gethsemane to the burial in the tomb.

O. Diverse Portrayals of the Crucified Jesus

As I said earlier, it is generally accepted that the Gospels were the product of development over a long period of time and so are not literal accounts of the words and deeds of Jesus, even though they are based upon the memories and traditions of those words and deeds. The Faith and preaching of the apostles have reshaped those memories. Each evangelist selected, synthesized, and developed the traditions that came down to him.

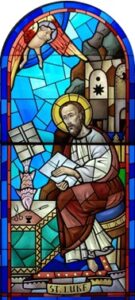

While there is only one Jesus, he is presented in different ways by the 4 evangelists.

Each one presents a different but not contradictory picture of him. This is particularly true in the way they paint their portraits of the crucified Jesus. Since Matthew differs only slightly from Mark in the passion narrative, I will confine myself to 3 different portraits: those of Mark, Luke and John. Let me describe those portraits briefly; to take each of them in detail would take several hours.

Mark portrays a stark abandonment of Jesus which is reversed by God in a dramatic way at the end. From the moment Jesus moves to the Mount of Olives, the behaviour of the disciples is portrayed in a negative way. While Jesus prays, they fall asleep three times. Judas betrays him; Peter curses, denying that he ever knew of him. All flee, with the last one leaving even his clothes behind in order to get away from Jesus – the opposite of ‘leaving all things to follow him.’

Mark portrays a stark abandonment of Jesus which is reversed by God in a dramatic way at the end. From the moment Jesus moves to the Mount of Olives, the behaviour of the disciples is portrayed in a negative way. While Jesus prays, they fall asleep three times. Judas betrays him; Peter curses, denying that he ever knew of him. All flee, with the last one leaving even his clothes behind in order to get away from Jesus – the opposite of ‘leaving all things to follow him.’

Both Jewish and Roman judges are presented in a very uncomplimentary light. Jesus hangs on the cross for six hours, three of which are filled with mockery from the onlookers; in the 2nd three the land is covered with darkness. Jesus’ only word on the cross is “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me.?”. And even that plaintive cry from a dying man is met with derision.

Yet, as Jesus breathes his last, God acts to confirm His Son. The Trial before the Jewish Sanhedrin concerned Jesus’ threat to destroy the Temple and his claim to be the messianic Son of the Blessed One. At Jesus’ death the veil of the temple is rent, and a Roman centurion confesses, ‘Truly, this was God’s Son.” This, for Mark, proves that Jesus was not a false prophet.

Luke’s portrayal is quite different. The disciples appear in a more sympathetic light, for they have remained faithful to Jesus in his trials. In Gethsemane if they fall asleep (once not thrice) it is because of sorrow.

Luke’s portrayal is quite different. The disciples appear in a more sympathetic light, for they have remained faithful to Jesus in his trials. In Gethsemane if they fall asleep (once not thrice) it is because of sorrow.

Even enemies fare better: no false witnesses are produced by the Jewish authorities; and three times Pilate acknowledges that Jesus is not guilty.

The people are on Jesus’ side, grieving over what has been done to him. Jesus himself is less anguished by his fate than by his concern for others. For example: He heals the slave’s ear at the time of the arrest; on the road to Calvary he worries about the fate of the women; he forgives those who crucified him; and he promises Paradise to the penitent ’thief’.

The crucifixion becomes the occasion of divine forgiveness and concern for others; and Jesus dies in peace praying, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.”

John’s portrayal presents a powerful Jesus who had earlier announced, “I lay down my life and I take it up again; no one takes it from me.”

John’s portrayal presents a powerful Jesus who had earlier announced, “I lay down my life and I take it up again; no one takes it from me.”

When Roman soldiers and Jewish police come to arrest him, they fall to the earth; they are powerless as he speaks the divine phrase, “I AM”. In the garden he does not pray to be delivered from the hour of trial and death, as he does in the other Gospels; this ‘hour’ is the whole purpose of his life. His self-assurance is an offence to the high priest; Pilate’s position is challenged before the Jesus who states, “You have no power over me.”

No Simon of Cyrene appears, for the Jesus in John’s gospel carries his own cross. His royalty is proclaimed in 3 languages and confirmed by Pilate.

Unlike the portrayal in other Gospels, Jesus is not alone on Calvary, for at the foot of the cross stand the Beloved Disciple and the Mother of Jesus. He relates these two highly symbolic figures to each other as son and mother, thus leaving behind a family of believing disciples.

He does not cry out, “My God, why have you forsaken me?” because the Father is always with him. Rather his final words are a solemn decision, “it is finished”; only when he has decided does he hand over his spirit. Even in death he dispenses life, as water flows from his body. His burial is not unprepared as in the other Gospels; rather, he lies amidst 45 kilos of spices as befits a king.

P. Which Version is the most accurate?

P. Which Version is the most accurate?

When these different Passion Narratives are read side-by-side, one should not be upset by the contrast or ask which view of Jesus is more correct:

– the Jesus of Mark who plumbs the depths of abandonment only to be vindicated;

– the Jesus of Luke who worries about others and gently dispenses forgiveness;

Or the Jesus of John who reigns victoriously from the Cross in control of the events.

All three accounts are given to us by the Holy Spirit, and no one of them exhausts the meaning of Jesus. A true picture of the whole emerges only because the viewpoints are different.

In presenting two different views of the crucified every Holy Week, one on Passion Sunday and one on Good Friday, the church is bearing witness to that truth and making it possible for people with very different spiritual needs to find meaning in the cross.

There are moments in the lives of most Christians when they need to cry out with the Jesus of Mark/Matthew, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me.?’ and to find, as Jesus did, that despite reasons to the contrary, God is really listening.

At other moments, they have found meaning in suffering by being able to say with the Jesus of Luke, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” and being able to entrust themselves confidently to God’s hands.

There are still other moments where we see that suffering and evil have no real power over God’s Son or over those whom he enables to become God’s children. This is the Jesus that is portrayed in the Gospel of John.

To choose one portrayal of the crucified Jesus in a manner that would exclude the other portrayals or to try to harmonize all the Gospel portrayals into one would deprive the cross of much of its meaning.

It is important that ……

some people be able to see the head bowed in dejection,

while others observe the arms outstretched in forgiveness,

and others perceive in the title on the cross the proclamation of a reigning king.

We adore you, O Christ, and we bless you:

Because by your Holy Cross you have redeemed the world.

A Summary of the Four Different Portrayals can be downloaded here: Passion Narratives -Portrayals