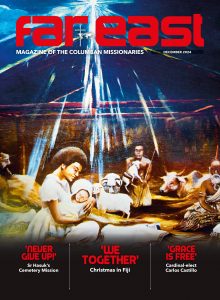

Former editor of the Far East, Fr Alo Connaughton, spoke to Cardinal Carlos Castillo, Archbishop of Lima, ahead of Pope Francis’ Consistory for new cardinals on 7th December 2024.

Carlos Castillo was born in 1950. He was 29 years old and had a degree in sociology when he began his studies for the priesthood in Rome. Back home as a priest in Peru, he worked mostly in poor parishes, while also a professor at the Catholic University.

Since 2019 he has been Archbishop of Lima, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, now divided into three more dioceses.

One of the important influences in his life was his former university advisor and friend, Fr Gustavo Gutierrez, and one of the founders of modern Latin American theology, who passed away aged 96 in October. Another was the Dominican Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1556), a tireless defender of the indigenous peoples of America, and the subject of his doctoral studies at the Gregorian University in Rome.

Cardinal Castillo’s Sunday Mass is broadcast by one of Peru’s national television stations and has an average of four million viewers each week. These Masses, which are also broadcast via the internet, show a man of great warmth and a skilled communicator. Covid, he says, had traumatic social and economic effects in Peru. It erased the gains made in the previous 20 years, when national poverty fell from 58% to 20%.

Out of a population of approximately 34 million, nearly 220,000 died from the virus, the highest percentage in the world. Though churches were closed, in crowded urban areas, many communities kept in touch with a priest in an open space, and creative ways were found to lead people in prayer, the Eucharist and distributing communion.

The return of widespread poverty and unemployment in the wake of the pandemic sparked protests, especially among young people in several cities across the country; resulting in the “massacres.” Protests in Lima, Ayacucho, Juliaca and other cities were violently repressed.

Some young people were murdered and dozens, mostly teenagers, were seriously injured by the government crackdown. The protests were not a resurgence of terrorism, as some claimed, but grassroots mobilisations against the chaos of the country’s leadership.

A Confirmation group out for a day’s reflection in Lima. Photo by Columban Fr Gabriel Rojas.

In a Holy Week homily, Cardinal Castillo lamented that: “It might have been possible to invent forms of dialogue, ways of dealing with situations and ways of really asking for forgiveness, ways that were authentic, and not just a lot of empty words.”

Do your homilies bring criticism I asked. “Yes, plenty,” he replies calmly. “In our preaching, our starting point is the Gospel and compassion for people, not a political platform. I have said many times, the Church is not of the right, nor of the left, nor of the centre, the Word of God is a call to all to reflect and change.” There was a prophetic tone, I suggested, in his homily the previous Sunday. It included comments on corruption and a plan to privatise water.

“Corruption is bad,” he said. “Seven recent presidents have ended up in prison. Another serious problem is poverty. The ambition and prejudices of a minority do not allow many to achieve a decent standard of living. For a while, the trickle-down theory of economics worked a bit and poorer people were able to improve their lives. But then Covid arrived. New investments often don’t bring new jobs – workers are being replaced by machines and computers. Of course money isn’t everything; being treated fairly and with respect is critical.”

In another recent homily, the Cardinal spoke of the need to reflect on how we ‘see’ God. Religions are largely human constructs. People who see God as a being to be feared develop a religion around that image. The ancient peoples of Peru called their god Wiracocha, the one who roared in the waters that came down from the Andes. The most enlightened of the early missionaries sought to help people discover the existence of a compassionate God. But elements of the old gods still remain. “We must constantly emphasise compassion, God’s gift is free, not bought or given in exchange. Grace is free; if it costs, it is a disgrace.”

Lima has always had a shortage of priests. I mentioned a parish where I had celebrated Mass the previous Sunday; it has 18 chapels and six more in various stages of construction. Soon there may be only two priests there. Cardinal Castillo referred to the primitive Church where the bishop celebrated the Eucharist and the consecrated bread was taken to the different communities.

Over time we became a Church where the priest was in charge of everything; communities dependent on priests. Circumstances will force change. In the parish I mentioned 300 teenagers, many of them university students, prepare for Confirmation by attending weekly meetings. Those responsible are youth leaders.

A Sunday Mass in one of the chapels in the parish of Los Santos Archangeles run by Columbans on the periphery of Lima. Photo: Fr Alo Connaughton.

“We have accustomed people to live the rites a lot. Receiving Baptism, First Communion and Confirmation was considered very important; but little was done to form people in the Christian way of daily life. Now we have to plan for lay leadership in a synodal Church.” Lifelong learning is essential. In many churches in Lima, the laity are in charge of “Sunday celebrations without a priest.” They are in charge of the prayers, readings and the communion service; they prepare the evangelical reflection. Part of the long-term planning in the archdiocese is courses to educate and train the laity.

Asked about his understanding of a synodal Church, he responded with an example. “We recently organised a Youth Day for diocesan youth groups. The organisers had planned a lot of prayer, silence, and confessions for the evening and the next day. They did pray but, remembering the wounds of the pandemic, we gave them the opportunity to express their own feelings and thoughts, and to listen to each other.”

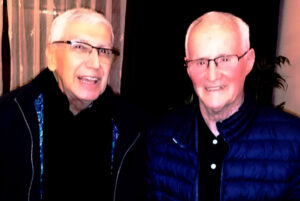

Cardinal Castillo with Columban Fr Alo Connaughton.

They did this in small groups and in a general assembly for two hours while the bishop listened – moved by the profundity of what he heard. Most of his recent pastoral letter to the youth was based on the words of the young people at the meeting. He referred to a letter Pope Francis wrote to Argentinian theologians in which he told them to put aside their heavy theology books and academic papers for a while and listen to what was happening at the grassroots. What the Spirit is doing today can also be discovered there.

Has Pope Francis influenced you? “Yes, first of all his vision: Francis is constantly thinking about the future from the complex present. A second thing is his humanity, his sensitivity to people. As bishop of Buenos Aires, he took the bus to the periphery to meet people, especially young people, every Sunday afternoon. He does not see himself as the possessor of all wisdom; he consults a lot.”

A procession in Lima. Photo: Fr Alo Connaughton.

With a heavy workload and not a few challenges, Cardinal Carlos frequently reminds himself of Pope Francis’ words that this role is not one of power, but of service. Although he carefully prepares his homilies for his televised Masses he often departs from the script to express a thought that has just occurred to him. He knows that it is often these spontaneous remarks that strike a chord with the faithful.

There’s a feeling that the Lord is using him as an instrument and he gets energy from the youth. While the Archdiocese of Lima has thousands involved in youth activities, there is just one priest directly involved in youth ministry. All the training, educational sessions and organisation is managed by the young people themselves. There is a lot of young life in the Church of Lima.

Fr Alo Connaughton is originally from Ballinacree, Co Meath. He was a missionary in Chile from 1974 to 1993 and then worked as the Editor of Far East magazine. He later served in Myanmar from 2004 to 2007 and taught at Saengtham College, Bangkok until 2022.

First published in the December 2024 issue of the Far East magazine. Please subscribe and support Columban missionaries. See https://columbans.ie/far-east-magazine/