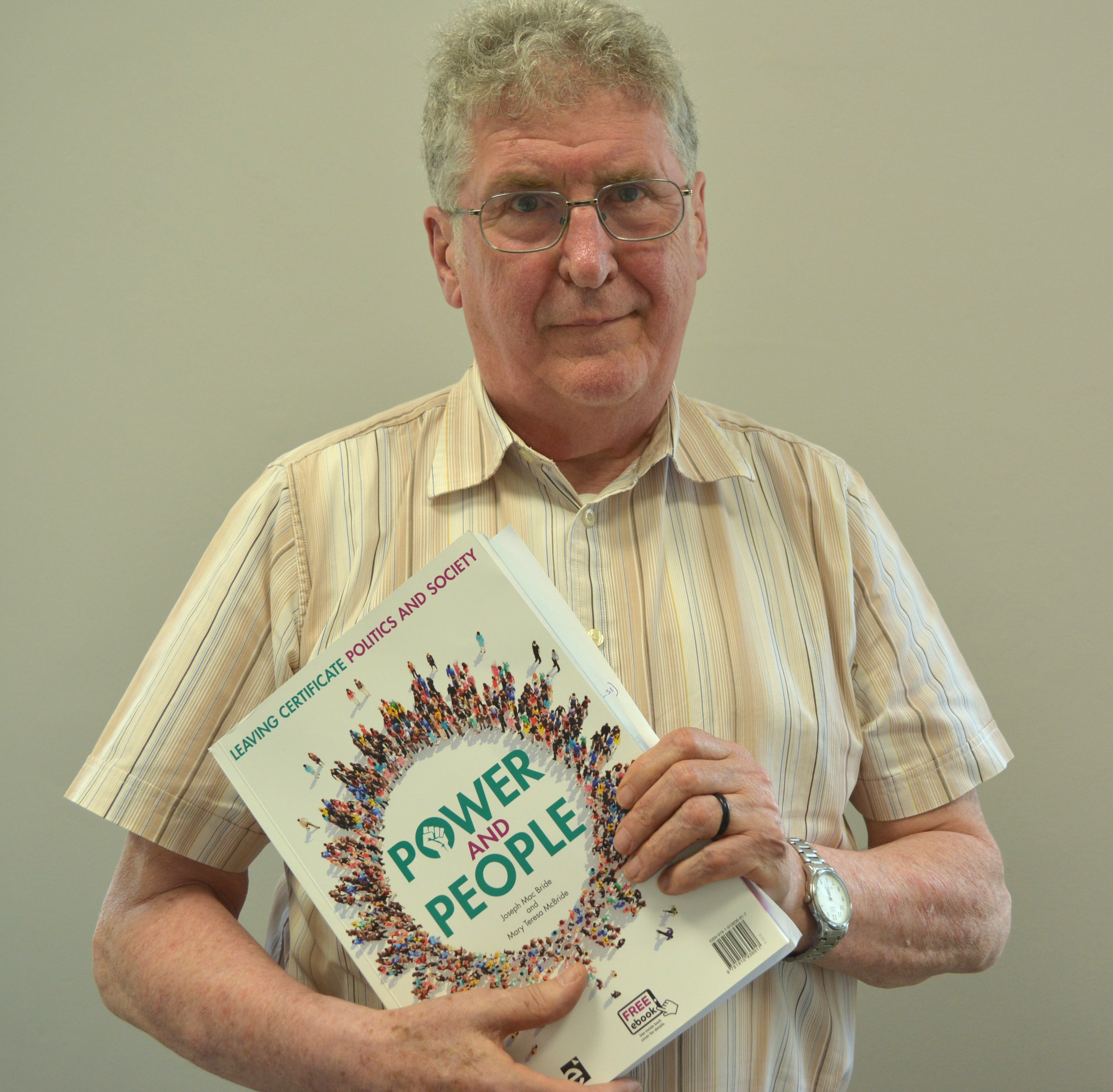

Columban eco theologian Fr Sean McDonagh is featured as a key thinker in the textbook for the new Politics and Society course for the Leaving Cert.

The subject has been examined for the first time in June 2018 after it was piloted in 41 schools from September 2016.

Politics and Society, according to educationalists, is intended to form part of the 2016 legacy, helping students to deepen their understanding of political and social issues, and helping the nation to develop a new generation of leadership across society. It aims to develop active citizenship among students, as well as informing them how social and political institutions work at local, national, European and global level.

From autumn 2018, the subject will be introduced as an option in all post-primary schools, coinciding with the centenary of Irish women getting the vote for the first time.

It is organised into four main areas: power and decision-making, active citizenship, human rights and responsibilities, and globalisation and localisation.

Fr Sean McDonagh has said he is “happy” to be associated with this textbook because, “It is good to have recognition for the work I’ve been at for close to 40 years. There are a number of key thinkers in it and as a missionary I am delighted to be recognised as someone who has something to say on the environment, sustainability and social justice.”

The new subject is, he believes, a “very valuable way of understanding society and many of the difficulties that challenge it today”. It looks at subjects like globalisation and sustainable development.

Fr Sean’s input came about when those who were drawing up the programme for the new subject two and a half years ago asked him if he would be part of the project because they had read some of his books including ‘Care for the Earth’.

“They liked my treatment of sustainability and they asked me to write something on that and so I looked at sustainability and living in an ecological way in our world today.”

Back in the 1990s, Fr Sean McDonagh was very much a solitary voice within the Church calling attention to the looming ecological crisis.

But under the pontificate of Pope Francis, he was part of the team who advised on the Jesuit Pontiff for his encyclical ‘Laudato Si’ and his work is now taken much more seriously and people are listening to him. He feels vindicated.

“In 2009, Benedict wrote the encyclical ‘Caritas in Veritate’ and it didn’t even mention climate change. Six years later Francis described ecological destruction as one of the most serious sins – that is six years and the Catholic Church isn’t known for moving very quickly!”

He pays tribute to the Columbans for giving him the opportunity to discover his interest in ecology and climate justice.

“I studied linguistics and anthropology in Washington and then I went back to the Philippines and taught in Marawi. I began working in Lake Sebu and I was there for 15 years. Over the years I saw logs in the water but I never put two and two together in relation to the impact of logging. Luckily, I came across people who were helpful including Thomas Berry. In that sense, if I had never gone to Lake Sebu I would never have written any of this.”

He highlights how at that time, ecology was very often very technical biology and biochemistry. “But I had lived in the place and had seen what was happening to the soil as a result of 25 years of logging. That life experience gave me the confidence to speak about it.”

But it is still an uphill battle getting people to grapple with the issue and this is most evident from the fact that nobody ever confesses to sinning against the natural world.

He also notes that though Laudato Si came out in 2015, and Amoris Laetitia in 2016, priests have little problem talking about the family but are a lot hazier on climate change.

He also notes that though Laudato Si came out in 2015, and Amoris Laetitia in 2016, priests have little problem talking about the family but are a lot hazier on climate change.

Ecological awareness “will not thrive if it is dependent on priests,” he suggests because “they have no experience or knowledge of it.” The Church needs to be willing to tap into the well-trained members of the laity who are versed in the encyclical and the issues it deals with, such as the destruction of species and sustainability into the future.

The Politics and Society textbook highlights some of Fr Sean’s areas of interests such as dependency on fossil fuels, unsustainable lifestyles, consumerism, growth in the human population and sustainability as well as his current research on the role of technology and the rise of AI.

He is currently writing a book which is due out later this year and will deal with this issue.

“In the 19th and the 20th centuries Northern Ireland was the shirt capital of Britain. The region hasn’t made any shirts for the last 20-30 years. About 30-40 years ago China had 3% of global production; it is now up to 25%. Jobs like those in Northern Ireland went to places where wages were much lower and so shirts could be produced at a much lower cost.”

“Robots and artificial intelligence pose a real problem. The jobs which gave countries like China and Korea an opportunity to get on the ladder are going to go. Moore’s Law tells us we double our computer skills every three years or four years and the same is true of artificial intelligence. This technology is going to destroy jobs like nobody’s business.”

“I am looking at the context – how do you run a society or a pastoral reality if half the people are unemployed? And those who are employed, are they part of the gig economy rather than real economies where you are able to live without being a pauper.”

“We talk here in Ireland about almost having full employment now. In the middle of the recession we were up to 16-17% unemployment. But when you drill down, what do they mean by full employment – are they zero hours contracts? Are they secure into the future? Are they paid enough money to actually live a decent life, build a house and do they get a pension? Those are the issues.”

He laments the fact that “Very few people in the religious world are actually looking at the impact of what these new technologies will be. This is something that is going to make extraordinary changes in society and most of them will be negative in the long term,” he warns.