In the week in which we celebrate our Foundation Day, Fr Cyril Lovett recalls the life of Bishop Edward Galvin, co-founder of the Missionary Society of St Columban.

Edward Galvin, the eldest of nine children, was born in Newcestown, Co Cork, Ireland. He had his father’s love of music and would play the violin and the harmonica. He was a natural mimic, a great gift for anybody who had to learn a foreign language, particularly a language like Chinese.

All his life he loved a sing-song and later, in China, whenever the priests gathered together, he himself could draw on a fund of songs. He grew up as a normal, healthy young man, showing few signs of the extraordinary gifts of leadership that would later distinguish him in China.

In 1909, a few short months before his ordination to priesthood in Maynooth, his father died – a severe blow to him and to all the family. He loved Cork and this parish of Murragh and Templemartin.

He hated to leave here: on the occasions when he came home on holidays from the missions he never told his family when he was leaving again – he simply disappeared one morning. He just could not face the pain of saying goodbyes. It is an indication of the man’s deep humanity.

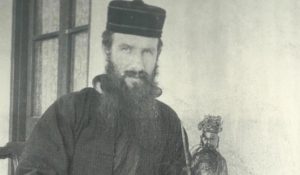

Once in China he quickly settled into pastoral work. He wrote, “If one wants to do anything among the Chinese, one must get rid of that air of superiority which Europeans are fond of assuming. The Chinese are quick to detect anything in that way. You cannot imagine how they love a European priest who treats them as equals. I must say I have found them a very lovable, and very different from anything I had expected.”

Once in China he quickly settled into pastoral work. He wrote, “If one wants to do anything among the Chinese, one must get rid of that air of superiority which Europeans are fond of assuming. The Chinese are quick to detect anything in that way. You cannot imagine how they love a European priest who treats them as equals. I must say I have found them a very lovable, and very different from anything I had expected.”

Galvin quickly saw that he needed many more priests and an organised group of supporters in Ireland if his efforts were to bear fruit. He wrote an enormous number of letters to priests, seminarians, relatives and friends.

For example, in the month of August 1915 alone he wrote more than 250 letters, and many of these were written by candlelight in the heat and suffocating humidity of a Chinese summer. He was a natural story-teller and a gifted letter-writer.

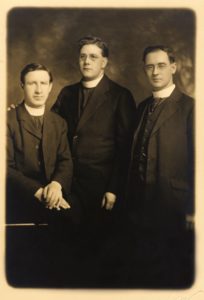

In April 1916, he and his first two companions, Joe O’Leary and Paddy Reilly, met in Shanghai and decided that Galvin should go back to Ireland to try and drum up support. In retrospect it seemed the most terrible timing for such a venture. The Easter Rising had happened a few short weeks earlier, and it was the middle of the First World War. In Ireland he was introduced to John Blowick, a young professor of dogmatic theology in Maynooth who also felt called to be a missionary.

We have always regarded Galvin and Blowick as co-founders of our Society. They had different but complementary gifts: Galvin was the leader, the action man; Blowick, the intellectual, with extraordinary gifts as an organiser.

We have always regarded Galvin and Blowick as co-founders of our Society. They had different but complementary gifts: Galvin was the leader, the action man; Blowick, the intellectual, with extraordinary gifts as an organiser.

With the help of very active group of diocesan priest friends they eventually gained the support of the Irish Bishops for the establishment of a missionary college. The extraordinary success of the movement, and the providential cooperation of so many people led Galvin to write to fellow-Corkman E. J. McCarthy in 1919, “What you or I or any man, big or small, may do is of little matter; it is God who is and has been guiding the whole work. Now more than ever his hand is apparent. John’s (Blowick) getting sick and Jim O’Connell’s illness was the greatest thing that could have happened… Mac, there is something very strange in this mission. It seems to be God’s very own and He is guiding it. He will enable it to complete the work he has destined it to do, independent of you or me or any other. Everything will come right. Have no doubt of that.”

When he was made bishop in 1927, he wrote again to E. J. McCarthy, “The one thing I am rather anxious about is the motto (on his episcopal coat of arms) and the one I want is ‘Fiat Voluntas Tua’ (Thy Will be Done). I hope that might constantly remind us here in China that we are not here to convert China, but to do God’s will, and we don’t know 24 hours ahead what that is.” In 1934 he was back for a visit to Newcestown.

He wrote, “I was in Newcestown many times. It has not changed. It is the same place you know. I liked to ramble around there and think of people who are gone … It was good to be home even for a little while. Nothing changes in Newcestown except the children. The youngsters spring up like daisies. I don’t know any of them.”

Bishop Galvin spent almost forty years in China, a longer time than any other Columban. He showed great gifts of leadership as a pastor to his Chinese flock and to his priests. There were always new crises to deal with viz. marauding bandits, floods, wars, famines, endless multitudes of sick and displaced refugees, and finally the Communist takeover.

He carried the main burden of responsibility. By the time he was expelled in September 1952, he was still only 71 years old, but, as photographs from the time show clearly he was totally exhausted.

In Hong Kong he was diagnosed with leukaemia, cancer of the blood, and when he died in Dalgan four years later he was still just 74. Those who later wrote about his all commented on his humility. Cardinal Spellman said of him, “He was a living saint, what more can one say?”

And Bishop Fulton Sheen writing in 1954 commented, “The impression that remains with me is of a man of evangelical simplicity which hid great spiritual power. He was simplicity itself and humility itself. … He was the type of man who could be a saint because he was not conscious of being saintly… In a bench of bishops he would not be the ‘outstanding bishop’, because he fools you, as a saint should fool you.”

Fr Cyril Lovett is a former editor of the Far East magazine.

Follow us on Twitter @IrishColumbans