Sometime towards the end of the 1960s while listening to the BBC World Service the name of John Hume came across the undulating air waves. His name was connected to what was described as unrest in Northern Ireland arising out of discrimination felt over time by the nationalist Catholic community.

Later newspaper cuttings sent by my mother showed pictures of John Hume being stopped and searched. There were many issues that needed airing such as voting rights, housing, unemployment and general discrimination felt by the Catholic and nationalist community.

As pleas and protests were ignored by the prevailing power in Northern Ireland, peaceful, non-violent protests grew. They were met by police brutality rather than dialogue by the prevailing powers.

As television reporting of events in Northern Ireland began to make headline news John Hume’s name among others began to catch public attention, none more so than the brutal image of police clubbing peaceful demonstrators. These pictures caught the attention of world and particularly the Irish diaspora.

Life in the Irish diaspora as in other diasporas was concerned with the issues that generally were the concern of wider populations in which they resided. Seeing these images of brutality against peaceful demonstrators carried out by a surrogate Northern Ireland government sanctioned by the British government scratched a dormant nationalist nerve in Irish hearts and particularly those in the Irish diaspora.

Irish people, aware of Ireland’s struggle for independence, were cognisant of many other post-war struggles for independence from British and other European colonial powers. The struggle for rights by black people in America did not go unnoticed. As black Americans hailed Martin Luther King and others Irish people began to place John Hume and others at the centre of peaceful struggle for rights in Northern Ireland.

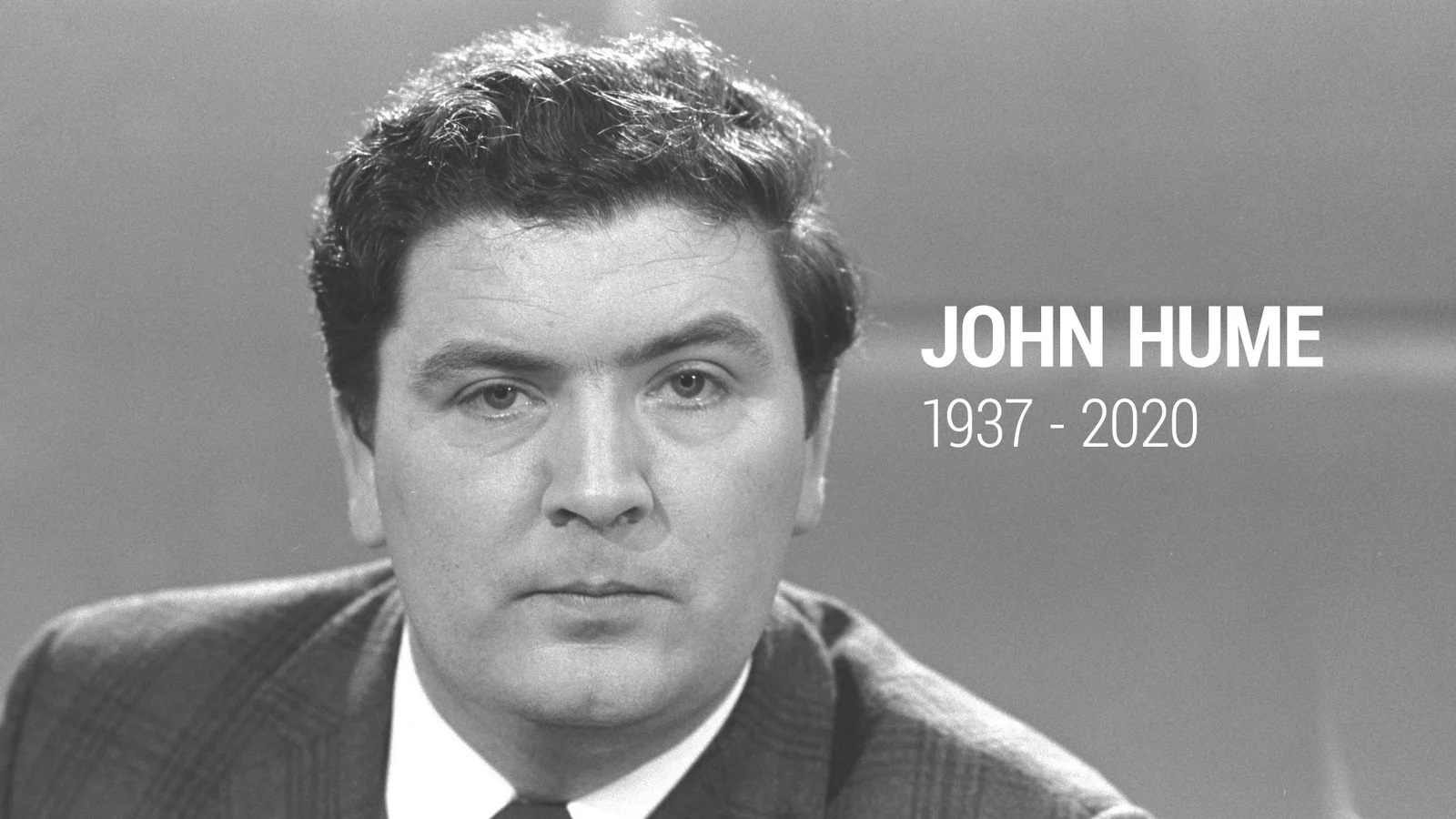

John Hume and others saw early on that political voices at the cusp of power both in London and Northern Ireland were paramount in bringing about peaceful change. John entered politics in 1969. In his early thirties John showed experience and competence in managing the public arena. He was well versed on the issues of the day at home and abroad.

He was articulate expressing an assertive confidence that many of the more senior Irish politicians lacked. John, like others in Northern Ireland, were beneficiaries of the new British education polices that gave access to third level education denied to previous generations.

They presented facts demanding policy changes at the highest level of government as opposed to pleading for compassion lacking facts.

John was not intimidated by the intolerance of the arthritic powers of Stormont and Westminster to maintain the status quo. Those powers did not recognise a different reality could be possible in Northern Ireland.

Rather than seeing the turmoil as an opportunity for change they saw it as an emergency thereby denying the possibility that something different could emerge. It was inevitable that if political change was impossible a descent into violence was inevitable. That was exactly what happened.

The resulting British government solution was a policy of security in itself a denial of possible change for something more equal, tolerant and democratic. A security policy will always have difficulty in searching for solutions because such a policy treats those seeking equality, justice and reform as suspect.

Arising from suspicion is a distrust, a legacy from colonial history in treating the colonised as dysfunctional and as such incapable of managing themselves. The plantation house casts a long shadow.

John and his colleague Seamus Mallon experienced this in the environs of British political power. So, their struggle to get recognition for the solutions they and others offered were not taken seriously. Both knew that and looked further afield in the halls of European Union and the corridors of the American Congress.

John was aware of the powers of diasporas to influence events in developments in the homelands and particularly in conflict situations. Diasporas are not neutral. Tensions in the homelands flow over on to diaspora streets. Sympathy with those perceived to be victims of oppression, discrimination and exclusion is easily translated into financial, political and social support.

The images of brutality by the police and military in Northern Ireland swayed sections of the Irish diaspora to support those who sought solutions through violence and terrorism. John set out to convince the political and economic powers in the diaspora that violence was not a solution that would bring about an inclusive peace in Northern Ireland, Ireland and Britain.

He struggled relentlessly throughout the violent necrophilia of the 1980s when hope seemed to be a scarce commodity. In the instances we encountered each other in the 1980s both at home and abroad he was of the firm opinion that any solution in Northern Ireland would come as a result of the influence of the political intervention of leaders in the Irish diaspora influencing a neutral power in the United States.

He concentrated on that avenue to influence possible solutions in Ireland. British colonial policy relating to Ireland held sway in Washington. John believed that had to be changed if a solution was to be found. His efforts eventually bore fruit resulting in better trusting relations between coloniser Britain, colonised Ireland and the new empire, the United States. The latter appointed a mediator who persevered in finding a solution.

John always seemed to be in an exhaustive state. His power was in his hope even though he was never certain of a definite outcome.

He believed that by making the dysfunctional system visible was a further step in finding a political solution. He was open to the ideas of writers, academia, social and political thinkers, historians, activists and the media. John’s motivation and hope was in uncertain peaceful solutions that he might somehow influence others in bringing about. His activism wasn’t about promoting his own image. At times he seemed to me to be coming up against walls.

However, he seemed to have an innate gift telling him that every wall had a door somewhere. John’s hope was a risky critical thinking hope born out of trust in a deep humility that recognised his gifts and fault lines, thanked God for them, and was prepared for the unknown, the possible, even failure. John was motivated to imagine a different future for Northern Ireland, Britain and the Irish Republic. He knew the past and he did wish to be its prisoner.

John was a star that did not dim after the sun came up. His resilient hope inspired me through the years to try the impossible even if it failed.

Follow us on Twitter @IrishColumbans