We, for our part,

have crossed over from death to life;

this we know because

we love our brothers and sisters.

1 Jn. 3:13

The Christian focus on the Cross has nothing to do with tragic consciousness. It is not a sick preoccupation with negativity in the place of an allegedly healthy involvement with life. It is the fruit of the deepest concern for life.

The memoria passionis will always be that which generates creative action for life. Some futurologists, focusing on possible nuclear or actual ecological disaster, have taken to using the world ‘holocaust” to designate our feared future. In doing this they seek to motivate people to action. It is a dangerous move.

We find it much easier to talk of our future victimhood than to focus on the past where we were the actors in perpetrating catastrophe. But such talk will never release the creativity needed to avert the feared future. The challenge will only be met by people who are keeping alive the memory and awareness of past and present suffering and victims, a concern that ensures that the evil will not keep happening.

True contemplation of the Cross involves us creatively in a story of suffering that is not over yet. But in the Cross we experience first and foremost acceptance, and it is this that opens up for us the possibility of confronting our own evil in depth. We are enabled to see that life is represented by the man on the cross, death by those who put him there. As Sebastian Moore put it some time back, (1) the voice from the cross is saying to us, “Can’t you see, what you are crucifying in me is the human being you are terrified to become?”

Jesus’ acceptance of death is the consummation of the compassionate love for life-denying people characteristic of all his living. It is the ultimate step in the eucharistic way of life reflected on above. No matter how we may have twisted things, this is the world and we are the people that have emerged from the loving creative Providence of God. To say “yes” to life, to receive it as gift, is to accept everything as an interconnected unity. If that ‘everything’ includes murderous rejection, then that too is to be embraced by love.

Because there is so little love of life in us, we are alienated from death and cannot help seeing disaster as incompatible with a loving Creator. Only when we become capable of offered suffering will the world not be too wicked for God to be good. And that moment happens for us when the compassionate death of Jesus is seen as the human dimension of a mystery whose God-dimension is a self-identifying of God with the suffering of all creatures. In the death of Jesus we discover that frail and mortal human life is what is most precious to God.

The Spirit is understood in the Old Testament as the divine energy of life. The Spirit it understood in the New Testament as the power of the resurrection. The deep continuity between the two lies in this: the life in question is now understood as response to the experience of the Spirit as unconditional Love. It is a life lived wholly and without reserve. Love unto death is what alone can show such unconditional love in history. The life of God is revealed in Jesus’ death as the surrender of love unto death: it must flower into resurrection.

It is not because of our hope in the resurrection that we are enabled to live wholly and without reserve. It is because we find ourselves enabled to live wholly – to accept, affirm and love fragile and mortal life – that we have resurrection hope for the world. This is the import of the message from the First Epistle of John with which we began this chapter. And we are enabled to live in this way by finding God in the love with which Jesus died.

I do not mean to suggest that anything of this could have been understood apart from the divine action of raising the crucified Jesus. The Gospel narrative evokes powerfully the hopelessness of the disciples after Calvary. As long as he was among them, his wholeness (sinlessness), his aliveness, irresistibly evoked their own deepest humanity. We are born creatures of unending desire, reaching out to all of life. But a diminished sense of self-worth cripples our desire, puts it “on hold,” and this is the shape of sin in us. Present to him, people came in touch with the fullness of their desire again. Once again, giving themselves fully to life and rejoicing in it became the truth of people. That is why it was so devastating when he was eliminated, wiped out by the imperial power as easily as you might swat a fly. They must have felt that they had been tricked into believing in life and love and God.

Normally, we do not experience death, we experience loss. Other people die; we carry on. But the involvement of the disciples with Jesus was so deep and intense that it makes sense to posit for them at this point an experience of death, an experience of radical hopelessness. And it was from that place that they were enabled to come back. And the shape of their living after they came back was of people who had their death behind them. I mean, people whose living was no longer controlled by fear of death or of anything. But nothing short of resurrection could effect this and lead them to affirm that Jesus was right about God.

But the truth they then discovered in the death of Jesus had been there all the time.

Those who have read as far as this and accept something of the truth with which we are struggling are hardly in danger of misreading the Gospel story at this point. But the tradition is far from unambiguous and I feel the need to touch on a few possible distortions.

The letting-go lived out by Jesus shows no trace of distancing from what is transitory or from people. Later Christian tradition has not gone unaffected by forms of “abandonment” which derive from the Stoics. The focus moves to “the vanity of the world” and of all passing things. An insufficiently profound modern-day Western encounter with Eastern wisdom seems heir to a similar refusal to accept the ambiguity of the transitory. Such interpretation of abandonment was characterized by Hans Urs von Baltasar as the most pernicious enemy of Christianity and of humanity in general because it paralyses every genuine involvement in earthly transitory life. (2) Rosemary Haughton (3) draws our attention to an opposite dynamic in the passion of Jesus: he is portrayed as giving the most detailed attention to the needs and reactions of others. His concern to the end is for what is happening to them.

This topic of abandonment has another meaning that leads into the heart of the message of Good Friday. It begins with Jesus’ agony in Gethsemane and culminates with the terrible cry recorded by Mark at his death. We seem to have an emotional block when it comes to looking at this deepest level of the suffering of Jesus, his experience of God-forsakenness. In retrospect, I think it may come from our unresolved God-image. We keep alive a God other than the One being revealed on Calvary, a God who could “intervene” in response to the prayer of his Jesus, and we find it too disturbing to think that God could intervene and did not. And so we deny the radicality of the God-forsakenness of Jesus.

But this stratagem blocks our access to the life-giving truth of Calvary. The truth is that the eclipse of God is real in a loveless world but that this fails to remove God. The traditional wisdom was that God was far from the sinners, from the accursed, from those who go down into the grave. (4) And so there were situations that could lead people to despair or justify them in distancing themselves from others adjudged to be God-forsaken. Jesus, ever faithful to the love of the Father, is “made to be sin” for us, according to Paul. (5) He experiences inwardly and without distancing himself from it the world from which Love has been abolished. He dies in inconceivably total darkness.

This is the most hideous moment in our history and also the most beautiful. “My God, why have you forsaken me?” In this God-forsakenness every trace of meaning is obscured. As a result of his dying like that, we now know that there is no human situation from which God is absent, no guilt that can modify God’s loving nearness and concern for us, nothing that can ever justify despair. This is the place where the discovery is grounded that in God there is no condemnation, that, for God, all people’s suffering is abhorrent.

Again, a word traditionally used in relation to the death of Jesus is ‘sacrifice’. It can be a dangerous word in the mouths of people who fail to love themselves and life to the extent that Jesus did. Just as we discussed earlier about the eucharistic way of Jesus as the manner in which all of life was gift to his radical faith and therefore to be received with thanks, so we must grasp that his saying ‘yes’ to all of life is what leads to his sacrificial way. To truly love people who are afraid of love is a very costing business. To accept to find ourselves through going out to others in love and taking them seriously in their otherness is to make their story and their pain part of our own becoming. This is the meaning of the sacrificial way of Jesus.

This path of Jesus, the Suffering Servant of God, grounds the ethic of love of enemies, of overcoming evil with good. It is difficult to find a language appropriate to this way of living but it matters that we do. Due to an insidious militarization of our everyday vocabulary, we can be tricked into “selling ourselves short.” Worse, since language forms consciousness, we may lose our original insight through mal-description. I am thinking of the manner in which we speak of tactics or even strategies of non-violence. This disguises the intrinsic meaning of a loving response by making it sound purely functional — how best to get things done. Nonviolence may be the best way to get things done but that is not why it is embraced: it is embraced because the enemy is loved.

To clarify the point, in that part of the world from which I come there is a very ancient tradition of how to cope with unjust oppressors. One simply goes and starves oneself on the oppressor’s doorstep. If redress is not forthcoming, the oppressor is left with the public guilt of one’s death. Jesus does not die like that.

Moved by the Spirit, our Church has in recent times publicly committed itself to the quest for peace and justice and come to recognize that without this quest there is no authentic evangelization. But if this is not to remain empty rhetoric Christian communities must live from a burning human centre where sin is swallowed up in the love of life, a love that includes our enemies. Through this alone can there be redemption of the times. Merely functional non-violence is not enough. Such a non-violent person places the onus for his/her death on the inflictor. We are challenged to the further step of appropriating our death in love for the inflictor and all people.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, executed by the Nazis in 1945, has left us a credal formula which gives some sense of what is involved in responding to the God of Jesus:

I believe

that God both wills and is able to

bring good out of everything, even the worst.

For this He needs people who are prepared

to allow everything to be served for the best.

I believe

that in every crisis

God wants to provide us

with as much power of resistance as we need.

But God never gives it in advance

so that we will entrust ourselves,

solely to him and not rely on ourselves.

All our anxiety over the future

must give way to such faith.

I believe

that even our mistakes and wrongdoing

are not fruitless

and that it is no more difficult for God

to cope with them

than with our presumed good deeds.

I believe

that God is no “timeless fate”

but, rather, that he waits upon

and responds to

our sincere prayer and responsible deeds.

The main liturgical action on this day is the Liturgy of the Cross. Many people precede this action by participating in the prayer form called the Stations of the Cross. Traditionally, there are fourteen stations. In our Introduction, mention was made of another series of Stations which gave us our theme for the week. These six Stations are now reproduced with some comment in the hope that these images can pull together and deepen the thoughts which have been shared.

Notes:

1 – The Crucified is No Stranger. London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1977.

2 – Life Out of Death, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985, p. 23.

3 – The Passionate Cod. London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1981, 147-148.

4 – Ps. 6:5.

5 – 2 Cor. 5:21.

Friday: Kissing Evil On the Lips by Fr Brendan Lovett from his book, ‘It’s Not Over Yet – Christological Reflections on Holy Week’, published by Claretian Publications.

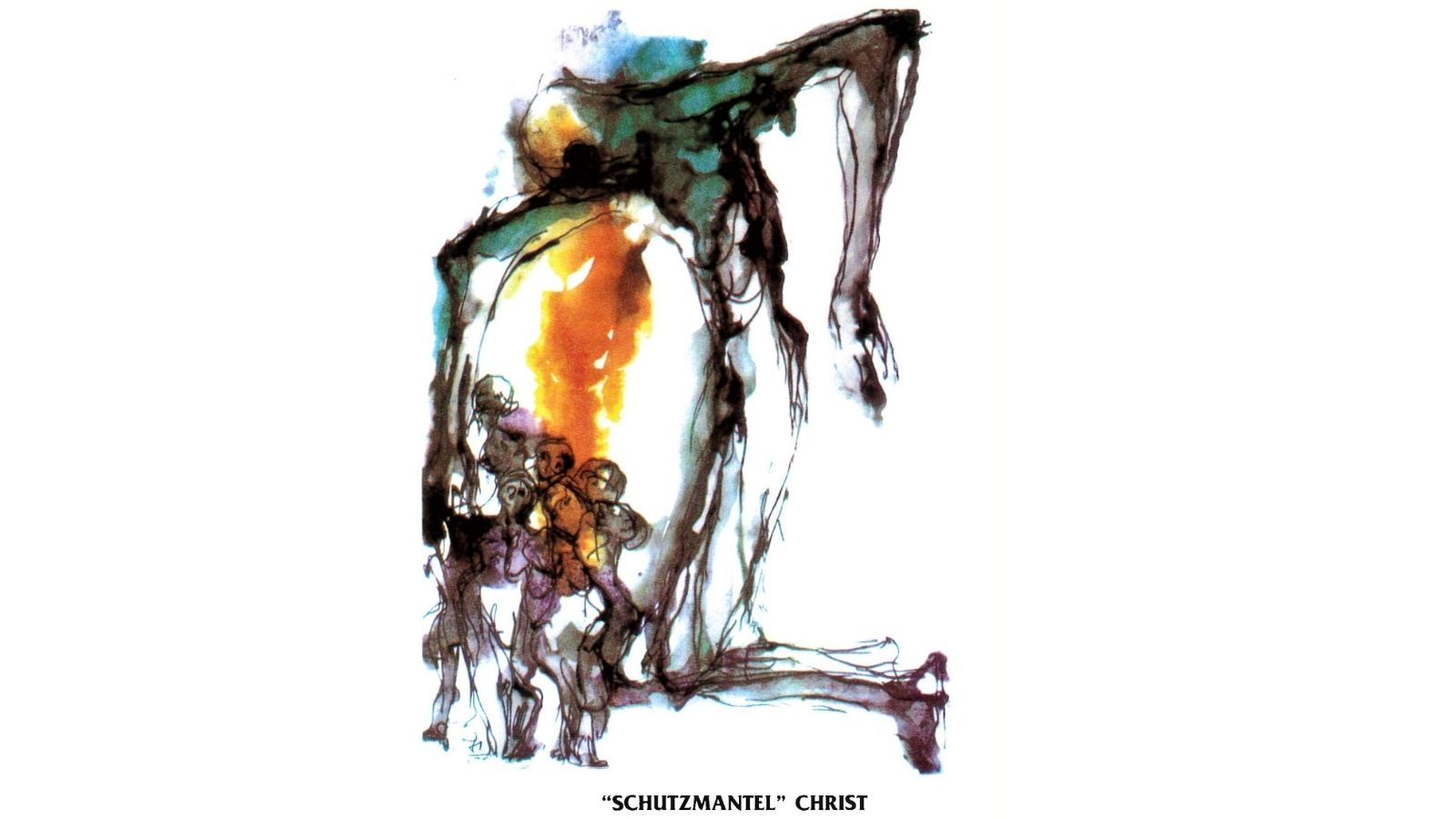

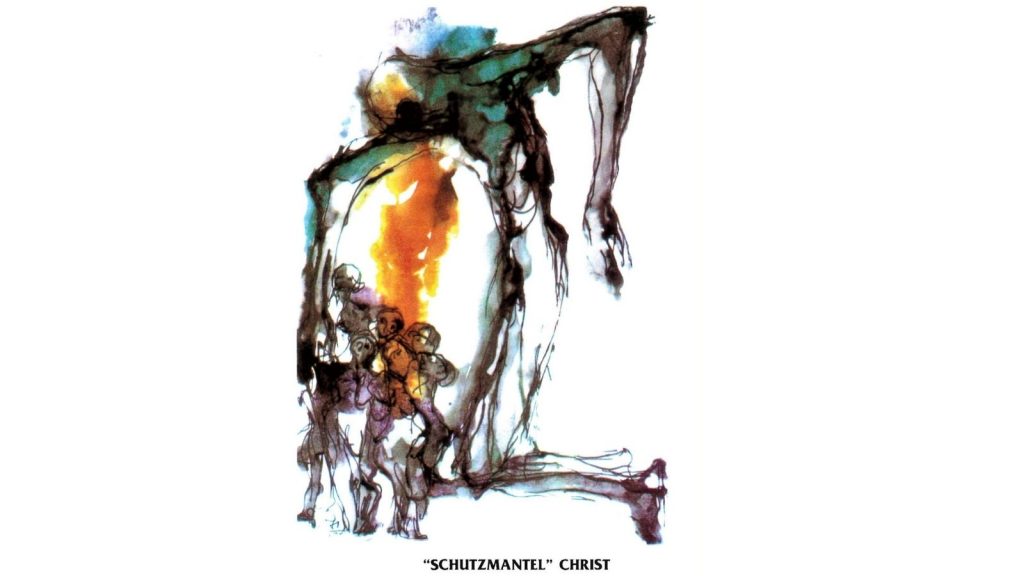

The drawing is by artist Roland Peter Litzenburger. One of a series of picture meditations before the Liturgy of the Cross on Good Friday.

“Overcoat” Christ:

The little phrase “for us” or “on

our behalf’ conveyed the first positive insight

of the early Church into the meaning of the

death of Jesus. The artist, by his bloodied but

protectively hanging image, gives expression

to the same insight.

On a bare

Hill a bare tree saddened

The sky. Many people

Held out their thin arms

To it, as though waiting

For a vanished April

To return to its crossed

Boughs. The son watched

Them. Let me go there, he said.