‘An Autumn Day in Dalgan with John Feehan’ was hosted by the Columban Ecological Institute on Saturday 6th of November 2021, writes Elizabeth McArdle.

Due to Covid restrictions, the day was restricted to Columbans only. The flyer promoted the day as: “A day to explore some of the wonders of this season of mists and mellow fruitfulness. Among the several themes we will explore are leaf fall and autumn colour, the production of seed for next year’s growth and the hidden world of woodland soil, where mushrooms and toadstools are particularly prominent at this time of year.”

When introductions and Covid regulations had been dealt with, the Autumn Day began with a power-point presentation. Many topics related to autumn were discussed and the science of leaf fall was described. We learned from John that leaves must fall from deciduous trees in autumn. If this does not happen, the energy required to maintain transpiration (the process by which plants give off water vapor) cannot be sustained over the winter months and the trees could die.

Since leaves are a big energy investment by the tree, all valuable nutrients must be saved before the leaves fall. Chlorophyll, (the green colouring in plants), is a very valuable nutrient and is drawn back into the tree. When the green colour in the leaves is gone, the beautiful autumn colours, which were there all the time, are revealed. These colours, which warm our hearts each autumn include the gorgeous yellows, reds, oranges and browns which we are all familiar with.

Cherry tree in Dalgan in full autumn glory 2021.

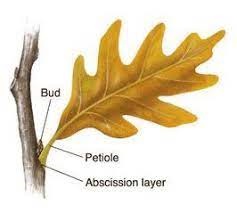

As leaves prepare to fall, they form an absission layer, which plugs the point just where the leaf joins the branch. This allows the leaf to detach without causing any damage to the tree. If this plug or absission layer did not form, it could leave thousands of small wounds on the tree, and this could give rise to infection which would enter and severely compromise the life of the tree.

Fallen leaves are a great source of food and shelter for many small creatures such as worms, mites, spiders, springtails, insect larvae, millipeds, centipedes and many other creatures with which we are not familiar.

On our field trip after coffee, we encountered many species of fungi in the Dalgan Woods and in the grassy areas around Dalgan. We were amazed with their colour, shape, and formation. We even found fairy rings and ‘Ohh’s’ and ‘Ahh’s’ were frequently heard as each new fungus of group of fungi were discovered.

On our field trip after coffee, we encountered many species of fungi in the Dalgan Woods and in the grassy areas around Dalgan. We were amazed with their colour, shape, and formation. We even found fairy rings and ‘Ohh’s’ and ‘Ahh’s’ were frequently heard as each new fungus of group of fungi were discovered.

Puff Ball and The Panther Cap

The praise was well deserved as fungi are so unique, they have their own special group within the kingdom of life. However, what lies beneath the soil or under the forest floor, is just as fascinating. Intertwined with tree roots, the fungi form a symbiotic relationship through which nutrients are exchanged. This very complex relationship benefits both the tree and the fungus. When we walk through a forest, it can be easier to pay attention to what is happening before our eyes but what we do not see is just as important and fascinating.

Puff Ball

There was more magic in the afternoon, as the microscopes were set up and our collected samples were examined at a higher magnification. Details of leaves, fungi and the small creatures which had made their homes therein were revealed. The microscopes gave us new eyes and it was extraordinary to see that which is not visible to the naked eye. Woos and wows were the main conversation of the afternoon as layer upon layer of wonder came into view.

To conclude, John gathered us around again to discuss the overall feelings of the day. While highlighting the perilous plight of the planet, he stressed that since most young people are no longer connected with a faith tradition, we as a faith community do not have the means of drawing them in to appreciate the wonder of the natural world. They have found other ways of doing this. This means we must work all the harder to achieve this.

The day ended with a greater appreciation of the miracle of autumn. Having spent part of the day outdoors, encountering nature at first-hand, we were left with a sense of wonder and awe. This is not surprising because we were in the presence of God’s primary revelation which is the natural world.

If you wish to read John Feehan’s most recent book, ‘Every Bush Aflame: Science, God and the Natural World’, it is available from Veritas, at Veritas House, 7/8 Abbey Street Lower, North City, Dublin 1, D01 W2C2 or veritasbooksonline.com

If you wish to read John Feehan’s most recent book, ‘Every Bush Aflame: Science, God and the Natural World’, it is available from Veritas, at Veritas House, 7/8 Abbey Street Lower, North City, Dublin 1, D01 W2C2 or veritasbooksonline.com

Mushrooms Observed in Dalgan Woods and Grasslands

White Fibercap

Inocybe geophylla, commonly known as the earthy inocybe, common white inocybe or white fibercap, is a poisonous mushroom of the genus Inocybe. It is widespread and common in Europe and North America, appearing under both conifer and deciduous trees in summer and autumn. The fruiting body is a small all-white or cream mushroom with a fibrous silky umbonate cap and adnexed gills: (reaching to the stem, but not attached to it).

White Fibercap

Clitocybe spp

Clitocybe is a genus of mushrooms characterized by white, off-white, buff, cream, pink, or light-yellow spores, gills running down the stem, and pale white to brown or lilac coloration. They are primarily saprotrophic, decomposing forest ground litter.

Wood Blewitt

Clitocybe nuda or the Wood Blewitt is found in autumn, among leaf litter in deciduous and mixed woodlands, often fruiting well into December if the weather is mild. Wood Blewitts are bluish when they are young and the caps, gills and stem are more a violet colour, but the cap surface soon loses its bluish colouration and turns ochre or tan from the centre outwards. However, the stem and gills still retain their bluish pigmentation even when fully mature. Rather surprisingly, Wood Blewits can be used to dye fabrics or paper a grass green colour rather than lilac or blue. To make a green dye, the fungi are chopped up and then boiled in water in an iron cooking pot.

Tawny Funnel Cap

Tawny Funnel Cap

This fungus is a saprobe growing on humus-rich soil, compost or conifer needles from summer to autumn. The cap grows up to 10 cm in diameter It is depressed in the centre or funnel-shaped when old and has a variable brownish colour which may be brown, orange or reddish.

The Judas Ear or Tree Ear

The Judas Ear grows throughout the year on living and dead trees and is most often found on elder trees. The name originates from the tradition that Judas hanged himself on an elder tree after he had betrayed Jesus. The outer surface of the lobed fruitbody is tan-brown with a purple tinge and covered with a fine grayish velvety down. The inner surface is smooth It is edible and when cooked and very popular in some eastern countries.

Lilac Bonnet

One of the most beautiful species of Mycena, this widely distributed mushroom is found decomposing forest litter under conifers (and occasionally under hardwoods) It features a strong, radish like odor and taste, and a cap that is convex, flat, or broadly bell-shaped at maturity. The colors of this species are extremely variable. When young and fresh, there is almost always lilac, or purple involved but as the mushroom matures other hues may predominate.

Waxcaps

These colourful mushrooms are named after the thick waxy gills that hang hidden below their caps. They come in a rainbow of colours from rich scarlets and lemon yellow to purples and green. Some species also have distinctive smells such as honey or fresh pencil shavings and are primarily associated with grassland. These include unimproved pastures, lawns, mountain and coastal grassland. They will sometimes crop up in woodlands but are much less common there.

Grey Funnel Cap

Clitocybe nebularis, commonly called the Clouded Funnell (and formerly more often referred to as the Clouded Agaric, is often found growing in rings in coniferous woodlands. It can also be found in deciduous woodlands and beneath hedgerows. Cap colours are generally greyish to light brownish-grey, and often covered in a whitish bloom when young. The surface of the cap is usually dry to moist.

Sulphur Tuft

Hypholoma fasciculare, commonly known as the sulphur tuft or clustered woodlover, is a common woodland mushroom, often in evidence when hardly any other mushrooms are to be found. This saprotrophic small gill fungus grows prolifically in large clumps on stumps, dead roots or rotting trunks of broadleaved trees.

Sulphur Tuft

Honey Fungus

Armillaria is a genus of fungi that includes the A. mellea species known as honey fungi that live on trees and woody shrubs. It includes about 10 species formerly categorized summarily as A. mellea. Armillarias are long-lived and form the largest living organisms in the world.

Puff Balls

Puffballs are fungi, so named because clouds of brown dust-like spores are emitted when the mature fruitbody bursts or is impacted. Puffballs are in the division Basidiomycota and encompass several genera, including Calvatia, Calbovista and Lycoperdon. True puffballs do not have a visible stalk or stem.

Candle Snuff Fungus

Xylaria hypoxylon is a species of fungus in the family Xylariaceae. It is known by a variety of common names, such as the candlestick fungus, the candlesnuff fungus, carbon antlers, or the stag’s horn fungus. This fungus is bioluminescent, meaning that it has the ability to produce and emit light. It often appears in clustered groups on dead/decaying wood such as deciduous stumps and branches (sometimes pine) and also causing root rot in hawthorn and gooseberry plants. It tends to follow on from other ‘wood rotter’ species that were previous residents of the substrate, such as the larger Honey Fungus and Sulphur Tuft mushrooms.

Shaggy Scalycap Mushroom

Pholiota is a genus of small to medium-sized, fleshy mushrooms in the family Strophariaceae. They are saprobes that typically live on wood. The genus has a widespread distribution, especially in temperate regions, and contains about 150 species. Pholiota is derived from the Greek word pholis, meaning scale.