The eco system of the mighty Mekong River is on the verge of irreversible collapse warns Columban missionary Fr Alo Connaughton.

The Mekong River, Mae Nam (mother water) Kong, as the Thais call it, starts from the melting snow of Tibet and flows for 2,800 miles through five other Southeast Asian countries on its way to the South China Sea. Students from Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos attend classes in the college where I work in Bangkok. The families of many of them are among the 60 million people that, in one way or another, depend on the Mekong for a livelihood. These days they have many reasons to be worried.

The biggest concern is the building of dams on the river. China has already built six huge dams on its section of the river in Tibet and Yunnan and has plans to build 21 more. This gives it considerable power to ‘turn a tap’ on or off, especially in dry seasons, as it controls much of the water in the upper stretches of the river.

Laos, ruled by a totalitarian regime since 1975, one of the poorest countries in the region, has about 1200 miles of the Mekong. It has built 46 hydroelectric plants along the Mekong and its tributaries and hopes to reach 100 functioning hydroelectric dams by 2030 (projections vary). Eleven are planned to span the main river.

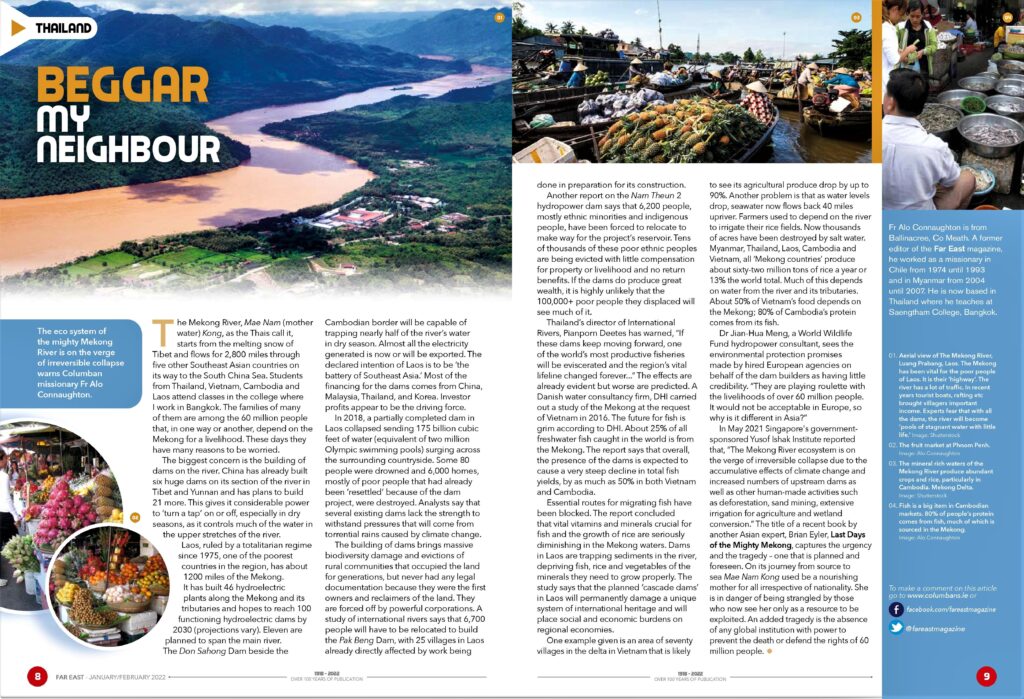

The mineral rich waters of the Mekong River produce abundant crops and rice, particularly in Cambodia. Mekong Delta: Image Shutterstock

The Don Sahong Dam beside the Cambodian border will be capable of trapping nearly half of the river’s water in dry season. Almost all the electricity generated is now or will be exported. The declared intention of Laos is to be ‘the battery of Southeast Asia.’ Most of the financing for the dams comes from China, Malaysia, Thailand, and Korea. Investor profits appear to be the driving force.

In 2018, a partially completed dam in Laos collapsed sending 175 billion cubic feet of water (equivalent of two million Olympic swimming pools) surging across the surrounding countryside. Some 80 people were drowned and 6,000 homes, mostly of poor people that had already been ‘resettled’ because of the dam project, were destroyed. Analysts say that several existing dams lack the strength to withstand pressures that will come from torrential rains caused by climate change.

The building of dams brings massive biodiversity damage and evictions of rural communities that occupied the land for generations, but never had any legal documentation because they were the first owners and reclaimers of the land. They are forced off by powerful corporations. A study of international rivers says that 6,700 people will have to be relocated to build the Pak Beng dam, with 25 villages in Laos already directly affected by work being done in preparation for its construction.

Another report on the Nam Theun 2 hydropower dam says that 6,200 people, mostly ethnic minorities and indigenous people, have been forced to relocate to make way for the project’s reservoir. Tens of thousands of these poor ethnic peoples are being evicted with little compensation for property or livelihood and no return benefits. If the dams do produce great wealth, it is highly unlikely that the 100,000+ poor people they displaced will see much of it.

The fruit market at Phnom Penh. Image: Alo Connaughton

Thailand’s director of International Rivers, Pianporn Deetes has warned, “If these dams keep moving forward, one of the world’s most productive fisheries will be eviscerated and the region’s vital lifeline changed forever…” The effects are already evident but worse are predicted. A Danish water consultancy firm, DHI carried out a study of the Mekong at the request of Vietnam in 2016. The future for fish is grim according to DHI. About 25% of all freshwater fish caught in the world is from the Mekong. The report says that overall, the presence of the dams is expected to cause a very steep decline in total fish yields, by as much as 50% in both Vietnam and Cambodia.

Essential routes for migrating fish have been blocked. The report concluded that vital vitamins and minerals crucial for fish and the growth of rice are seriously diminishing in the Mekong waters. Dams in Laos are trapping sediments in the river, depriving fish, rice and vegetables of the minerals they need to grow properly. The study says that the planned ‘cascade dams’ in Laos will permanently damage a unique system of international heritage and will place social and economic burdens on regional economies.

One example given is an area of seventy villages in the delta in Vietnam that is likely to see its agricultural produce drop by up to 90%. Another problem is that as water levels drop, seawater now flows back 40 miles upriver. Farmers used to depend on the river to irrigate their rice fields. Now thousands of acres have been destroyed by salt water. Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, all ‘Mekong countries’ produce about sixty-two million tons of rice a year or 13% the world total. Much of this depends on water from the river and its tributaries. About 50% of Vietnam’s food depends on the Mekong; 80% of Cambodia’s protein comes from its fish.

Fish is a big item in Cambodian markets. 80% of people’s protein comes from fish, much of which is sourced in the Mekong. Image: Alo Connaughton

Dr Jian-Hua Meng, a World Wildlife Fund hydropower consultant, sees the environmental protection promises made by hired European agencies on behalf of the dam builders as having little credibility. “They are playing roulette with the livelihoods of over 60 million people. It would not be acceptable in Europe, so why is it different in Asia?”

In May 2021 Singapore’s government-sponsored Yusof Ishak Institute reported that, “The Mekong River ecosystem is on the verge of irreversible collapse due to the accumulative effects of climate change and increased numbers of upstream dams as well as other human-made activities such as deforestation, sand mining, extensive irrigation for agriculture and wetland conversion.”

The title of a recent book by another Asian expert, Brian Eyler, ‘Last Days of the Mighty Mekong’, captures the urgency and the tragedy – one that is planned and foreseen. On its journey from source to sea Mae Nam Kong used be a nourishing mother for all irrespective of nationality. She is in danger of being strangled by those who now see her only as a resource to be exploited. An added tragedy is the absence of any global institution with power to prevent the death or defend the rights of 60 million people.

Fr Alo Connaughton is from Ballinacree, Co Meath. A former editor of the Far East magazine, he worked as a missionary in Chile from 1974 until 1993 and in Myanmar from 2004 until 2007. He is now based in Thailand where he teaches at Saengtham College, Bangkok.

This article was published in the January/February 2022 issue of the Far East magazine. Please subscribe and support the mission work of the Columbans. Just €10 for a digital subscription or €20 for print. Online subscriptions here: https://columbans.ie/product/far-east-magazine-yearly-subscription/