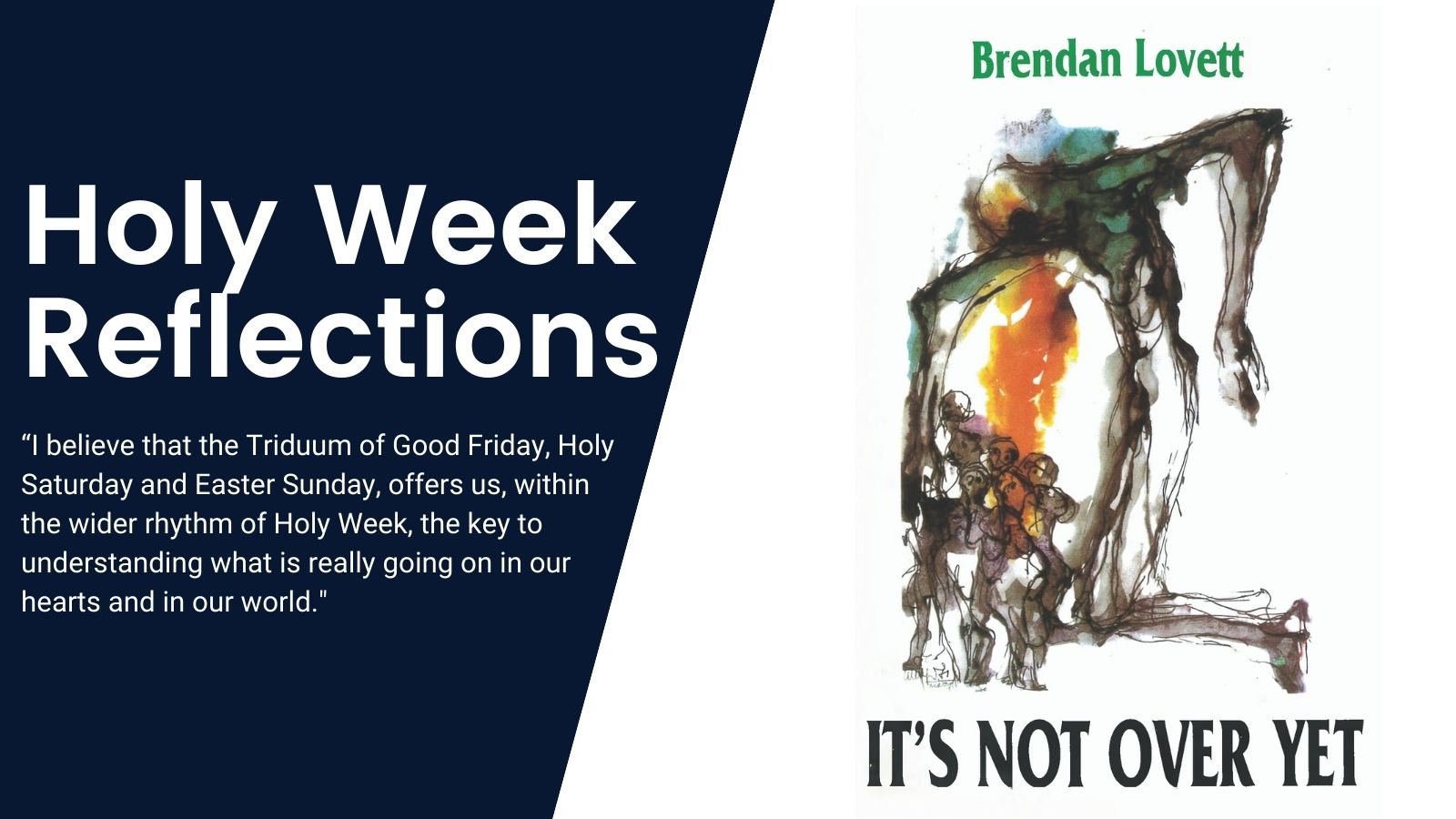

To help us enter into the meaning of Holy Week, we will be reproducing every day next week a reflection by Columban missionary, Fr Brendan Lovett, from his book, ‘It’s Not Over Yet – Christological Reflections on Holy Week’, published by Claretian Publications. Here, we publish the Introduction and some comments from Fr Lovett.

“I believe that the Triduum of Good Friday, Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday, offers us, within the wider rhythm of Holy Week, the key to understanding what is really going on in our hearts and in our world. It invites us to discover the truth of heart’s desire, beyond all compulsive misnaming, and it reveals the source of our compulsions in enabling us to experience that our fear was unnecessary.”

“Crucial to the whole process is our coming to sue that we were mistaken, wrong in our deepest assumption about God and, consequently, in our assumptions about the world we inhabit. Wrong, especially, about death, and about God in relation to death. These are the assumptions result in our living our lives ‘under the reign of death’.”

“Our healing is coincident with the discovery of how much we have falsified God. But how could we, trapped into our self-hatred, ever discover how wrong we were in projecting a remote and angry God? Only by experiencing the true face of the Love that is there for us. It is to such an experience that the liturgy invites us.”

Holy Week Reflections by Fr Brendan Lovett can be found here: https://columbans.ie/category/reflections/

INTRODUCTION

Great numbers of people followed,

many women among them,

who mourned and lamented over him.

Jesus turned to them and said,

‘Daughters of Jerusalem,

do not weep for me; no,

weep for yourselves and for your children.’

Luke 23:27-28

Some years ago in a small town in Germany a group of young people decided to try to pray their way through the Lenten season. As the weeks went by, they felt the need to contribute something of their reflections to their community during the culminating liturgies of Holy Week.

Living in their town was an artist. He did not frequent their Church, or indeed, any church that they knew of, but they decided to ask his help. He listened to what the

young people had to share, entered into their understanding of the Passion of Jesus, and agreed to help.

He produced six large paintings on paper to be hung in the church. He had a title for the series which conveyed the young people’s understanding: IT IS NOT OVER YET. (1)

He wished to convey that the Passion of Jesus is to be placed within the ongoing story of the passion of humankind, in solidarity with the suffering people of all times and places. It cannot be understood apart from this wider on-going story.

I think that the young people were profoundly correct. When we look to the Gospels for guidance, the first — and only — prohibition we meet with in the Passion narrative is in the word of Jesus: ‘Do not weep for me; no, weep for yourselves and your children.’* (2) It can be subtly self-serving, a way of massively missing the point, to indulge in tears for the sufferings of Jesus. Just as it is inadequate to indulge in tears for the suffering of anybody else.

Something more robust than pity is demanded of us in the presence of suffering and that something is involvement-in-the-situation-with-a-view-to-changing-it. The gospel prohibition is against the easy, spontaneous emotion that provides a quick release of the tension and that is almost invariably misdirected.

Annie Dillard (3) tells of watching the hopeless struggles of a doe tied by the neck to a tree and destined by her local hosts in the upper reaches of the Amazon to be the main dish for supper. While she was watching the doe, she was in turn being watched by her three male American companions. They were amazed at her lack of emotional response to the plight of the doe. One said that, had his wife been present, she would have made a scene and demanded that “somebody do something about it.”

Annie Dillard, in turn, was amazed at them. She had spent so many years of her life unflinchingly contemplating the reality of the natural world and its suffering. She knew this suffering to be an unavoidable part of the reality and the beauty of a material universe. She knew that she herself and the three men would eat and thereby live from this beautiful helpless creature that same evening. She would not allow herself the luxury of an irrelevant response.

There is something more to be learned, to be entered into, here: a deeper schooling of our emotional life. For the whole of the previous two years, she tells us, she had a newspaper cutting attached to her washroom mirror. It recounted the story of an

unfortunate man who was the victim of an industrial accident and nearly burned to death. After unspeakable suffering he lived — only to become the victim of an almost identical accident thirteen years later.

Once I read that people who survive bad burns tend to go crazy; they have a very high suicide rate. Medicine cannot ease their pain; drugs just leak away, soaking the sheets, because there is no skin to hold them in. The people just lie there and weep. Later they kill themselves. They had not known, before they were burned, that the world included such suffering, that life could permit them personally such pain. (4)

The Gospel never invites us to pity. We read, rather “Feed the hungry, clothe the naked.” We are invited to active involvement. The Gospel is in sharp contrast with our present-day culture which encourages people to “have a good cry,” to easy emotional indulgence without costly involvement. This culture manipulates our emotions without challenging us to change things. Our own involvement in suffering is what leads us to change things.

If an event is simply past it is not possible for us to be involved in it. The same is true of the passion of Jesus. This is not an event isolated from the rest of human history. It will never be understood unless placed within our ongoing reality. It is only if we understand it in continuity with all the suffering of the world that we can be properly involved in the passion of Jesus. It follows that the path to proper involvement in the passion of Jesus is openness to deeper involvement in the suffering of our world now.

It is not over yet.

How, then, does the passion of Jesus relate to the on-going story of human and sub-human suffering? Just as a lens can concentrate the sunlight, diffusely present to everything, into an intense white heat, so the passion story of Jesus has the power to illumine the truth of the suffering that is omnipresent in creation and history and the truth of God in relation to suffering.

This is not to suggest that there are easy answers to be had. In the face of the mystery of birth and death there are no answers. But there is a meaning to be sensed by entering more deeply into the reality of our lives and this can be more than enough to keep us going.

The language of our faith tradition suggests that the deepest truth of our lives is contained in the story of this man’s suffering and death. This language suggests that we can come to see the cross of Jesus as the deepest meaning of everything that is going on in our world. But, again, we will only come to recognize this if we are open to the present suffering of our world.

The wailing women of Jerusalem had, simply through their wailing, no part in the real event: they, like the rest of us, were part of the truth of what was happening to Jesus but they were unaware of their involvement. Jesus’ injunction that they weep

for themselves is an invitation to realize that they are already involved in what is happening. Only through such a realization can they fruitfully respond to his suffering.

We must try not to repeat the women’s mistake. If we will dare to be honest and try to take the whole world into our gaze, we may come to weep for the right things.

Notes:

1 – The artist’s name was Roland Peter Litzenburger. We used reproductions of these

paintings as picture meditations before the Liturgy of the Cross on Good Friday and they are reproduced in Chapter Five.

2 – Luke, 23:27-28. Quotations are from the New English Bible. There is a further prohibition at the end of the passion narrative where the risen Jesus forbids Mary Magdalene to cling to him. A similar message against missing the real point is contained there. Since the two prohibitions “frame” the passion story, they can be read as a directive on how we are to read the whole story.

3 – Teaching A Stone To Talk. New York: Harper & Row, 1983.

4 – Teaching A Stone p65