We two alone will sing like birds i’ the cage:

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness: so we’ll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we’ll talk with them too,

Who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out;

And take upon’s the mystery of things,

And if we were God’s spies.

Shakespeare’s King Lear

Those people who embrace the Jesus Principle, the secret of living as life-through-death, know no more than anybody else the shape of the future. They cannot visualize, either for themselves or for others, the resurrection they believe will surely follow. It is no part of authentic faith to be able to picture the future. In fact the opposite is the case: authentic faith has as its content the knowledge that God can be trusted with the future and it is willing to let the Mystery remain mystery. But we cannot live without symbols and people of faith have always dreamt of the future that God is bringing to our world. If they happen to be poets their dreaming can supply us with the images that can nourish us and give us orientation in life.

Jesus inherited such guiding symbols and through his life and death gave them a new content. The “kingdom of God” is the metaphor of definitive salvation seen as a society of brothers and sisters, freed from all oppression, where every tear is wiped away. Within this perfect community, the “resurrection of the body” is the symbol for the complete salvation and happiness of the individual in his or her distinctive corporeality, the source of other’s enjoyment of us. And, finally, the symbol of “the new heaven and the new earth” expresses the transformation of an undamaged ecology, the enduring condition for experiencing truly human salvation.

And there are poets in our own time who can suggest images to nourish hope.

One day people will touch and talk perhaps easily,

And loving be natural as breathing and warm as sunlight,

And people will untie themselves,

as string is unknotted,

Unfold and yawn and stretch and spread their fingers,

Unfurl, uncurl like seaweed returned to the sea,

And work will be simple and swift

as a seagull flying,

And play will be casual and quiet

as a seagull settling,

And the clocks will stop, and no one will wonder

or care or notice,

And people will smile without reason,

even in winter, even in the rain.* (1)

But resurrection faith is not a matter of dreaming. It is waking from our dream of reality to the reality in the dream. It is a way of living which proclaims the truth of the Risen One to the world. And the shape of this way of living is simply a continuation of the way Jesus responded to ordinary people in this sense of the God of the Kingdom. Resurrection faith is shown in our engagement for the people God loves wherever their dignity and life is being threatened. The resurrection of Jesus cannot be separated from his career and death. In the New Testament, the new thing, that the Father does for Jesus is understood, first and foremost, as recognition of the intrinsic and irrevocable significance of his lived proclamation of the Kingdom. (2) He was right about God. It follows that the primary witness today to the truth of his resurrection lies in the quality of commitment and hope displayed in the lives of Christians.

Where Christians follow in prayer and liberation in the footsteps of Jesus, there is no crisis of resurrection faith. But in the absence of such following I would wish to identify with the strong sentiments of Edward Schillebeeckx:

On the other hand I must say with all my heart; it is better not to think that God is true, better not to believe in eternal life, than to believe in a God who belittles, keeps down and humiliates men and women with an eye to a better hereafter. (3)

To let God easter in us is, as Lear says to Cordelia, to take upon ourselves the mystery of things. It is to see everything, especially people, as carriers of the mystery, the Mystery present at the heart of our Universe and all its manifestations. It is to be in touch with the depth, the promise, which all life carries, the deep down truth of things. If we respect and cherish creation we sense the promise it carries and no matter what such respect costs us we know it is worthwhile. We become willing to die a little so that there may be more life. In this way we enter into the path of Jesus, the path of life through death.

The text with which this chapter begins comes from the closing scene of King Lear. The old man, crazed by suffering brought on him by his own failure to recognize real loving, is overcome by delight at the discovery that the love of Cordelia had never been withdrawn. In the joy of forgiveness, he projects with supreme sanity the shape of their future living. It s a picture of the world as perceived and lived in the light of the resurrection. Through the sacramentality of Cordelia’s love, he is in touch with the mercy that embraces all things; he has become aware of how much people need each other and must tender and receive forgiveness constantly. He reveals enormous compassion for everyone, even as he sees through the folly of which he himself had been guilty – gilding the butterfly. Human beings are created fragile and vulnerable and, as such, are beautiful. But we cannot believe in the beauty of being vulnerably human. We try to protect ourselves through disguise – possessions, achievements, status. We hide the very thing that makes us desirable. Lear’s compassion flows from a sense of the mystery of things, the forgiveness that is the air we breathe, God loving people.

To let God easter in us involves a break with our fixed roots in the socially-induced unquestioning sense of “the way things are.” We need to go beyond ourselves in a way that is not flight or evasion but rather a discovery of the possibilities of transformation of the everyday world. The whole process is suggested in the opening of Wallace Stevens’ “The Man with the Blue Guitar”:

The man bent over his guitar,

The day was green.

They said, “You have a blue guitar,

You do not play things as they are.”

The man replied, “Things as they are

Are changed upon the blue guitar.”

And they said then, “But play, you must,

A tune beyond us, yet ourselves,

A tune upon the blue guitar

Of things exactly as they are.” (4)

If, like Jesus, we learn to receive all as gift and do not cling to anything, we may come to “let go” and thus be liberated into the fertility of newly-germinating life.

Fertility was a great theme in the Easter Vigil liturgy. This liturgy needs to be considered as a self-contained liturgy which developed quite independently of the Holy Thursday and Good Friday liturgies. The latter grew out of pilgrimages to the Holy Places associated with Jesus. The Easter Vigil was the great liturgy of the early Church. It took its form from the Jewish Passover meal and grew out of the elaborate celebration of Easter morning as the heart and life of all Creation. It nearly died out over the centuries but in 1956 a courageous attempt was made to recover it in its full splendour. (5)

Liturgical patterns need generations to take root. Neither here in the Philippines nor anywhere else in the Catholic world has the Vigil succeeded in winning pride of place in the liturgical year. But it may come. It may be that the well-intentioned revision of the ritual in 1970 is partly to blame for the slowness with which this celebration is regaining hold. The revision cut back on the excessive number of readings – there were twelve – but it also cut back on the crucial symbolism of life and fertility, death and new life, which had been faithfully recovered in 1956.

It makes sense to talk of an emasculation of the symbolism because the 1956 liturgy was strongly sexual. Only thus could it celebrate the transforming power of creation in us. All the symbols come from the opening chapter of the Book of Genesis. The font symbolizes the womb of mother Church fertilized by the phallic form of the lighted candle which is plunged ever deeper with rising tones by the celebrant. When the candle had reached its deepest point, the celebrant was instructed to breathe on the water in the form of the Greek letter psi, first letter of the term for life, psyche. The symbolism is of fecundity and regeneration. The fertilization of the virgin Church is related to the fertilization of the primeval waters, the waters of chaos. We are given a creation story centred on Christ. The birth of new members, the catechumens, is linked to the birth of the universe. This powerful and primitive ritual takes place in the darkness of the night.

By contrast, the 1970 ritual says that the priest “may” lower the candle into the water and his action is accompanied by a theologically impeccable prayer that all who are buried with Christ in the death of baptism may rise again in newness of life. The richness that the old symbolism was trying to communicate is gone. We cannot afford to lose it.

Sexuality is the form of being human, it is the mark of our vulnerability, the manner in which we are at each other’s mercy in terms of our becoming and growth. There is a connection between sexuality and death. The message of both is one and the same: we do not have our lives of ourselves, we are not our own. We belong to something greater than ourselves and our happiness lies in our letting go into that. Our habitual trivialization of sexuality is the sign of our inability to accept its true meaning. We creatively live sexuality by accepting the truth of our mutual belonging and by accepting it radically, my flesh for the life of the world.

The old Easter Vigil, then, was not being crude in its choice of symbols: it was being precise. Sexuality and death are much too closely intertwined for people to be able to make sense of one without the other and the Easter message reveals the truth of fecundity as life through death. The life of the Spirit in people does not shun death or try to preserve itself; it embraces its death for the sake of life. Hope, fertility and suffering go together. The more intensely and unreservedly we love life, the more intensely we experience the pain of creation and the deadliness of death. Not to love and not to hope is to shrink from this pain. But in hopeless striving to make ourselves immune to the pain we become enclosed in an infertile, living death. Jesus, dying on the cross, embodied life: we, putting him there, are embodying death.

Not just the Vigil but every eucharist and every sacrament is a celebration of the world as a resurrection world. Sacraments exist to give us a toe-hold on reality. Jesus was rejected by the crucifying world: we meet him now by standing against the crucifying world and with its victims. The life that comes out of death remains nevertheless life out of death, forever marked by its path: he is living but “as though slain” (Rev. 5:6,9,12; 13:8). That is why the Cross, contemplated in the power of the Spirit, remains our best picture of the resurrection, it remains the dominant Christian symbol. It is there that death is swallowed up in love. And it remains forever true that we experience resurrection in trying to love as He loved.

Notes:

1 – A.S.J. Tessimond, “Day Dream” in The Collected Poems ofA.S.J. Tessimond, ed. Hubert Nicholson, Reading, Whitenight’s Press, 1985, p. 48.

2 – It is the resurrection also that makes possible the identification of Jesus in relation to the Father and this confession on his identity is central to Christian faith. But this recognition through his resurrection is inextricably tied up with the way Jesus lived and died.

3 – Jesus in Our Western Culture: Mysticism, Ethics and Politics. London: SCM Press, 1987, p. 28.

4 – Collected Poems. London: 1955.

5 – Cf. Herbert McCabe, Cod Matters, pp. 101-113.

Saturday: Let God Easter in Us by Fr Brendan Lovett from his book, ‘It’s Not Over Yet – Christological Reflections on Holy Week’, published by Claretian Publications.

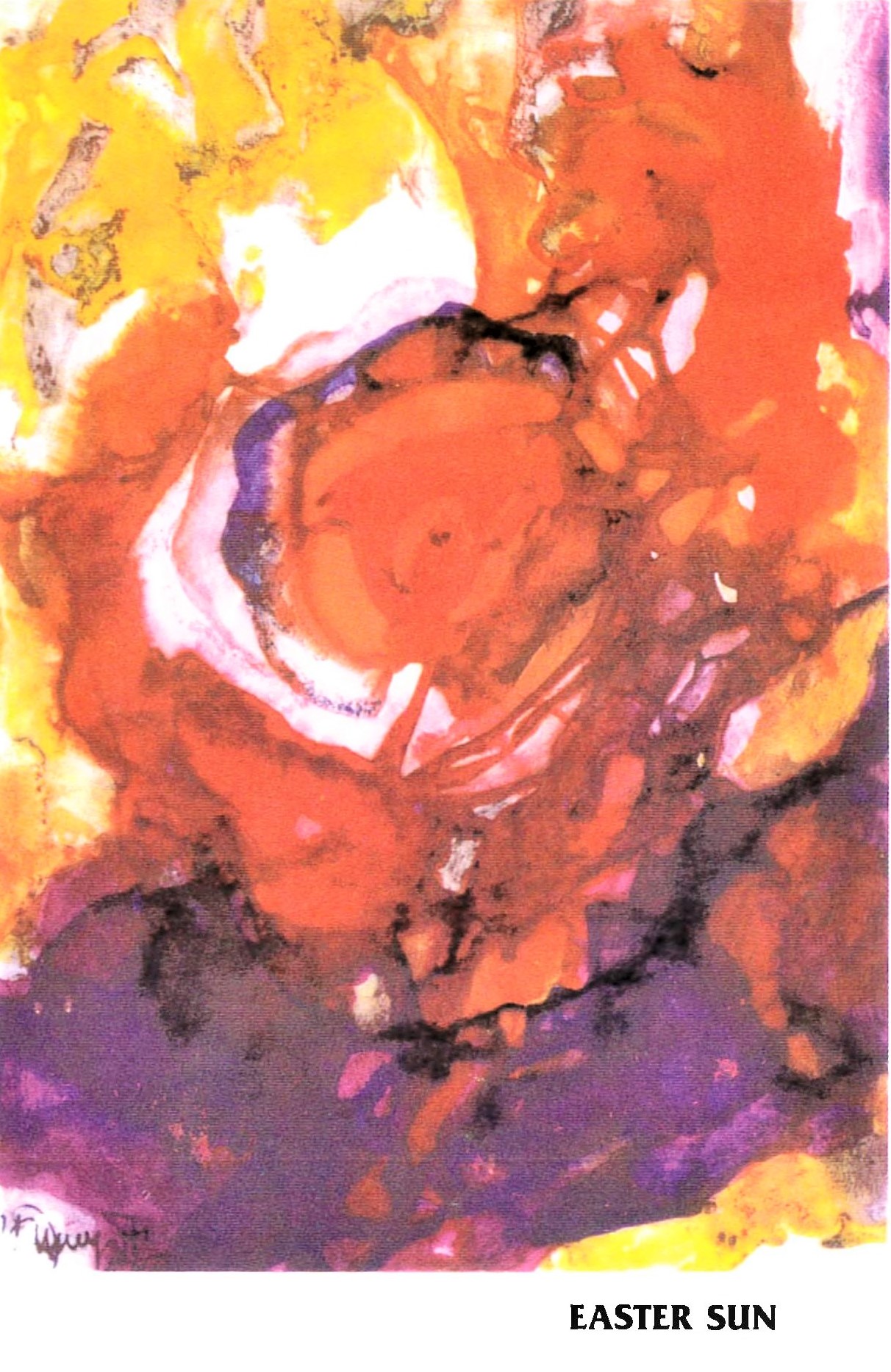

The drawing is by artist Roland Peter Litzenburger. One of a series of picture meditations before the Liturgy of the Cross on Good Friday.

No.6 Easter Sun: The artist has created an Easter sun from the full spectrum of interwoven colours. The passion colours are integral to the vibrant life of the whole. The culmination of God’s creation includes our whole life and death. Our fear was unnecessary.

The Easter message is not about a triumph over death. Formulated as such a triumph, the message would confirm us in seeing death as something that we rightly fear, something that should not be, as punishment, and this would serve to reinforce our deep suspicion of God who allows such ‘evil,’ rather than be our healing into joy. The Easter message is about the ‘swallowing up’ of death in life, the Lamb standing as if slain, the Risen One bearing wounds that clearly are mortal, yet experienced as intensely and wonderfully alive.