In truth, in very truth I tell you,

a grain of wheat remains a solitary grain

unless it falls into the ground and dies;

but if it dies, it bears a rich harvest.

The man who loves himself is lost,

but he who hates himself in this world

will be kept safe for eternal life…

During supper, Jesus, well aware that the Father had entrusted

everything to him … rose from table, laid aside his

garments, and taking a towel, tied it round him. Then he

poured water into a basin, and began to wash his disciples’

feet and to wipe them with the towel.

John 12:24-25; 13:3-5

It may seem strange to speak of the cross as the ground of our hope before we have mentioned resurrection. But it was the presence of the God of Jesus in the cross that we had in focus above and it was that faithful presence that came to be recognized as operative in the resurrection. When we say that there was “more” going on at Calvary than our redemption, this is a way of pointing by Jesus. Resurrection faith is the Christian form of belief in creation.

There is eternal life before death. The Gospel stories show it in the living unto death of Jesus. The Spirit of God is what is manifest in Jesus’ affirmation of life and it is the eternal life of God that is present as the surrender of love unto death. This is what has a future: “if we become incorporate with him in a death like his…” is what Paul stresses. (1) This is the death that flows from the acceptance, the affirmation and the love of frail and mortal life. (2)

And this is the message of the first of the two quotations from John’s Gospel above: fruitfulness, fertility, being a life-giver, all are tied up with dying, letting go for the sake of life. This dying can only be done in hope. Hopelessness, on the other hand, goes with infertility. Wherever we try to preserve ourselves and withdraw from costly caring for heart-breakingly fragile and vulnerable life, we embark on a sort of living death, immune to pain, closed to God.

The ground of our hope is God identified in Jesus with God’s cherished creation. Jesus did not preach and live “God” but rather “the kingdom of God,” i.e., the future God is bringing to a loved world. The manner of witnessing to this “nearness” of God-for-us was a life lived wholly and without reserve at the service of vulnerable life. As this offer of the coming kingdom met with rejection, Jesus was faced with certain death. We do not know how he managed to integrate his approaching death into his proclamation: he may have had to do it in the darkness of faith. But he did it. And consistent to the end he celebrated with his friends a last festive meal that had the shape of a farewell in hope. We certainly cannot understand the significance of this meal independently of all the other meals that Jesus had shared with people, independently of the way of life which had brought him to this meal marked by death. But this does not prevent the meaning of his message from being embodied as clearly here as anywhere else in the story.

We are given two traditions regarding this meal, that of the Synoptic Gospels and that of St. John’s Gospel. John concentrates on Jesus’ washing of the disciples’ feet. (For the first time this week, our reflections have come to coincide with the liturgical action of the day, Holy Thursday). I would like to enter into the meaning of this action by reflecting on a Gospel story to which it is closely related. It is the story of a woman whose action caused Jesus to predict that it would never be forgotten wherever the Gospel was being proclaimed. The force of his saying that seems to be that the woman’s action revealed a grasp of what the Gospel is all about: this woman got things right.

Mary of Bethany anticipates the foot washing scene by her anointing of Jesus. In doing this she embodies the kind of discipleship Jesus elaborates in John 13-17. There is a mistaken assumption that the sense of Jesus’ resurrection is so strong in John’s Gospel that it seems to deny or at least belittle the reality of death. Nothing could be further from the truth. None of the synoptic Gospels stresses in such detail the deadliness of death. The stench of decomposition hovers over the story of Lazarus. The threat of death follows Jesus on every step of his earthly journey. We are never allowed to forget it for one moment. It is explicit in the context of the Bethany narrative (3) and in Jesus’ grim reminder that “you will not always have me.” In the face of looming death Jesus alone seems able to name what is happening. Jesus and this woman.

Instead of the paralysis and inability to comprehend that has gripped the companions of Jesus, this woman does not go into denial. She grasps intuitively the certainty of the approaching death and she responds. She asks no questions. In the face of death, one must love life. One must love the threatened life and show in every way possible how precious that life is. In any other context her action might seem extravagant. But in the face of certain death it is singularly appropriate and it is acclaimed as such by Jesus: “When she poured this oil on my body it was her way of preparing me for burial.” (4) Her reckless pouring of a pint of expensive ointment on Jesus’ feet (Matthew says on his head) enacts for Jesus the truth that love is stronger than death. In this creative response to the deadliness of death Mary of Bethany embodies the faith that is at the heart of the Gospel. It believes in life as the gift of God and refuses to betray that life even under the threat of death. To trust God and to serve life in its integrity are interchangeable expressions for the one gift of faith that Jesus sought to bring to birth in us.

If we are right to see Mary’s action as anticipating the foot washing scene, it follows that we should see in her the kind of discipleship later developed in the discourse of chapters 14-17. It is a discipleship of service. In his own action of washing their feet, Jesus gives the disciples an example of what it means to follow him. It means to be a servant of life, to pour out our lives for the sake of life. The endless questions and apparent incomprehension of the disciples at the meal reveal as much as conceal their real pre-occupation, their grief at their impending loss, (5) their implicit cry Why does it have to be like this?” The discourse is meant to comfort them. There is no farewell discourse at the meal in Bethany. Mary did not need any.

She shows in her action a knowledge that death is only overcome by confronting its hard reality face to face. She tells us that death is ugly and strong, that love is stronger, that the love of God can be trusted in the death of Jesus.

Our feet are surely the humblest part of our bodies. The washing of feet may seem very inadequate as a symbol to carry the whole message of Christian living. But if we open ourselves to participation in this ritual, especially if we make it reciprocal, we may find otherwise. Death and resurrection cannot be the truth of one moment only. Precisely as Gospel truth it must be manifest somehow in every moment, the principle of all living. The shape of all authentic living is death/resurrection willingly undergone. In John’s Gospel the washing of the feet is an instance of the kind of everyday dying that real living demands. This is how it can point, for John, towards the Eucharist.

In our growth to adulthood we exert great effort towards being able to do certain basic things by ourselves. Our sense of independence and privacy depends on being able to take care of bodily hygiene without dependency on others. We expect others to be able to take care of themselves also in these matters. So to kneel and wash another’s feet involves us in some humiliation, in something even ridiculous. Perhaps even more, to allow another to wash my feet entails a loss of hard-won independence, a loss of privacy and thus of dignity for me. Either way this ritual brings us to a tiny laying down of life. (6)

And Peter resisted this. He was then told that this was the only way to continue in communication with Jesus. Either we accept to die into and for one another or we never truly live the gift of life. This is the connection with sin in the incident. To wash and allow ourselves to be washed signifies the opposite of sin’s refusal of death, sin’s insistence that others, always others, should have to be victimized, to die, so that I may be preserved. What might it mean to live humanly?

The enormously real sin dimension of our history obscures the positive message of the Gospel. It is not easy to distinguish in the one historical event of the passion what it is that flows from the mystery of iniquity and what from the love of the Father responded to by Jesus. It is not easy but it is necessary. Many of the Fathers of the Church (7) had a straightforward answer to the question as to whether the Son of God came to act or to die. They said Jesus was born in order to be able to die. Free and loving response to the God of life means allowing the seeds of eternity to be sown in the soil of the world and having the kingdom of God burst forth in this soil. We must die so that there may be more life.

What justifies this voluntary laying down of life, then, is our desire to witness to our unity in the one flesh, to witness to the truth of our belonging to each other and to our earth. But this is the truth denied by our elaborate social structures of privilege and discrimination. It will not do to forget sin. I believe that it can be misleading to say that Holy Thursday, the Eucharist, is about unity: it is primarily about disunity, sin. As everybody except bourgeois liberals can see, there is no real unity in the human world. This means that the only authentic unity in the world must necessarily take the form of the struggle against that in the world which makes unity impossible. We can only express unity sacramentally and the sacramental signs of Holy Thursday take us into the real depths of both sin and love, the meal (love-feast) marked by death on the torture machine. (8)

For faith, unity is a mystery; we can only talk about it with reference to God and what God is trying to effect in human history. As McCabe puts it, the ultimate unity of people is only to be found in God and the real God is only to be found in unity between people. (9) And this unity does not exist in our world. Our only approach to it is the solidarity of the poor and exploited against their oppressors. This is both true and not enough. (10) *

To know God through the prism of our sinfulness is still not to know God. The option for the poor is necessary because of sin. Hence the Kingdom can only be expressed sacramentally, in hints and gestures towards the future, in gestures that convey the costly direction towards the future but cannot simply depict that future. Paul’s Corinthian communities forgot the complexity. They apparently wanted to celebrate the Eucharist in a way that was not marked by death, thereby losing one half of the symbolism. Whatever they may think, Paul tells them, in coming together it is not the Ford’s supper that they eat.11 Paul knows this because of the exclusion of the poor.

In the Eucharist we celebrate in symbol what we ought to be but clearly are not. But if we enter the celebration as a chance of conversion, forgiveness of sin, then we do come in touch with that for which we hope.

The eucharist is the great sacrifice of praise by which the Church speaks on behalf of the whole creation. For the world which God has reconciled is present at every eucharist: in the bread and wine, in the persons of the faithful, and in the prayers they offer for themselves and for all the people…. The eucharist thus signifies what the world is to become: an offering and hymn of praise to the Creator, a universal communion in the body of Christ, a kingdom of justice, love and peace in the Holy Spirit. (11)

As Mackey puts it, eucharistic praxis is the Christian alternative to war. (12) (13)

Notes:

1 – Rom. 6:3-5.

2 – Cp. J. Moltmann, Cod in Creation. London: SCM Press, 1985, 275.

3 – Mt. 26:4; Jn. 11:57, 12:10.

4 – Mt. 26:12.

5 – Jn. 16:6.

6 – An unpublished talk by Timothy Radcliffe, referred to in McCabe, (Cod Matters, p.89), throws more light on the meaning that this action may have hard for the disciples. Feet were normally washed by a servant with one notable exception: a wife could wash her husband’s feet ‘not because she was a servant but because they were one body’. Radcliffe quotes from a story, Joseph and Asenath, roughly contemporary with Jesus, in which the bride will not let anyone else touch Joseph: “Your hands are my hands and your feet are my feet and I will wash them, and no one else will touch them.” Just as in the Eucharist, the action of Jesus in a footwashing that inverts social order and expectations is primarily about our becoming one body.

7 – Prominent among them were Tertuliian, Gregory of Nyssa, and Leo the Great.

8 – Cp. the reflection on Tuesday above. Cf. the rich treatment given by Herbert McCabe, God Matters, 76-89.

9 – God Matters, 78.

10 – “We have to see that there is no other God to be known except. ‘The Lord your God who brought you out of the land of slavery…’; and yet this is not yet to know God. The Church must be the Church of the poor – this is the sign that she is on the way to the Kingdom; it also shows that she is not there” (McCabe, God Matters, 79).

11 – 1 Cor 11:20. Revised Standard Version.

12 – W.C.C., Faith and Order Paper no. 111, Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry. Geneva: 1982, 10-11.

13 – Modern Theology: A Sense of Direction. Oxford: 1987, p. 185.

Thursday: Dying We Live by Fr Brendan Lovett from his book, ‘It’s Not Over Yet – Christological Reflections on Holy Week’, published by Claretian Publications.

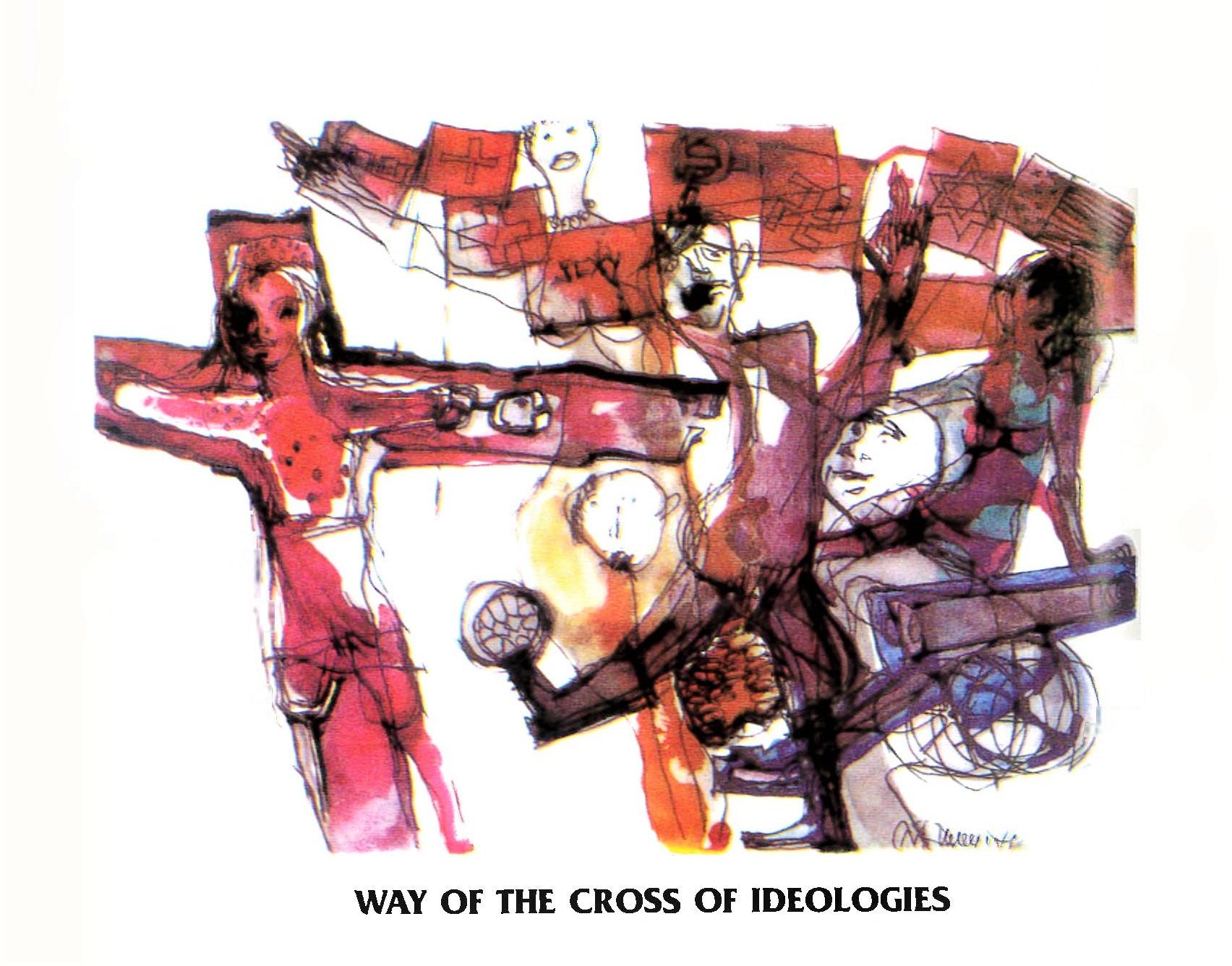

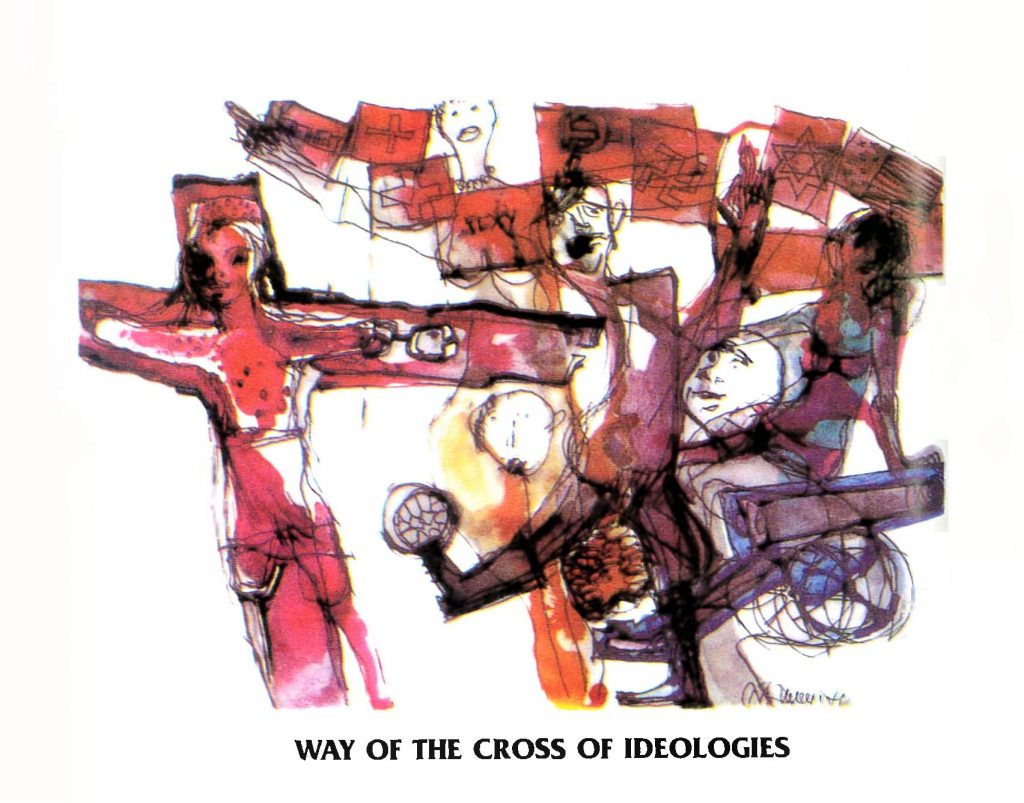

The drawing is by artist Roland Peter Litzenburger. One of a series of picture meditations before the Liturgy of the Cross on Good Friday.

No. 4 Way of the Cross of Ideologies: This is the most complex drawing, suggesting all the interlocking systems which bring suffering to our contemporary world. People are made victims of the systems which are meant to serve them.

The thalidomide child

victim of the cut-throat struggle for market supremacy

in an economistic world whose only law is profit…

foreground to another “cross”

made up of all the “-isms” of the day

which are invoked to justify bringing death to people

nationalisms, political economies, liberty –

all masking the commodification of everything,

symbolized in the sexual exploitation of women

(the totally unfeeling, vacuous face of the man)…

and, to balance the picture,

the “political” cost of such falsification of life:

the endless repression of life

institutionalized in the armaments industry,

where the highest return on your investment is assured

and life-symbols – the bikini girl –

are placed at the service of selling death.