The men who were guarding Jesus mocked at him.

They beat him, they blindfolded him, and they kept

asking him, ‘Now, prophet, who hit you? Tell us that.’

And so they went on heaping insults upon him…

There were two others with him,

criminals who were being led away to execution;

and when they reached the place called The Skull,

they crucified him there, and the criminals with him,

one on his right and the other on his left. Jesus said,

‘Father, forgive them; they do not know what they are doing’.

Luke 22:63-65; 23:32-34

A fragment of a prayer of Huub Oosterhuis lingers in my mind:

Lord God,

we see the sins of the world

in the light of your only son.

Since his coming

to be your mercy toward us

we have come to suspect

how hard and unrelenting

we are toward each other…(1)

It is in the light of his coming that the real dimensions of the evil that imprisons us and that we perpetrate on each other can be frighteningly explored. I drew attention already to the starkly simple language of the passion narratives. The writers do not exaggerate for emotional effect. What we find then is not to be read as literary embellishment. And what we find is an extraordinary amount of unbridled hostility and hatred toward the victim. How is this to be understood and what light does it throw on the cycles of evil in which we find ourselves caught? The way into this is, once again, to bring the passion narrative into connection with everything else we know of our world.

John V. Taylor suggests that a relevant start t today might be a perusal of the reports of Amnesty International. Here we will discover that every day, throughout our world, with the effective blessing of governments, helpless women and men are being tortured and brutalized, apparently for no other reason than that they are helpless and at the mercy of those who have power over them. There must be more going on and if we will look more searchingly into our own hearts we may discover what it is. If we are to read the words of Jesus in v.34 above as anything more than love trying to make excuses where there is no room for any excuses, there must be room for an insight into us which he possessed.

Some years ago, Sebastian Moore suggested that reading John Le Carre’s ‘The Spy Who Came in from the Cold’ could enable the English reading public to recover a sense of original sin. The novel communicated well how simply maintaining the reasonable status quo is what brings death to the innocent. Our normal stereotypes of good and evil are hardly adequate to the truth. It was, after all, the respectable establishment of church and state that carried out the judicial murder of Jesus.

Familiarity can blind us to the obvious so that it takes an artist to enable us to see again. As cover illustration for his Yes To God, (2) Alan Ecclestone features a picture of a steel sculpture by Louis Osman. The original stands two meters tall. At first glance it is a cross with a circle. We then see that the circle has jagged teeth, that the vertical beam supports two powerful steel springs which attach to one half of the circle and would cause it to snap shut on the other half were it not for the restraining trigger, the palm frond. We are looking at a carefully made machine, designed like a bear trap. But this, the artist tells us, is a man trap. It is designed to cut in two any human being who reaches for the palm frond (John 12:13), who reaches for a world without domination or exploitation. It is the frightening instrument whereby a society maintains its ‘law and order’ against those who long for a more humane order.

We are helped by the artist to realize again the historical function and reality of the cross within the Roman Empire. The cross was an instrument of death by torture. Its public dimension gives the clue to its functioning. As the most humiliating and painful way of killing that could be devised, it was meant to demonstrate the total power of the Roman state and its radical intolerance of any who failed to appreciate the benefits of the Pax Romana.

But it is not the Roman state which we need to have in focus. All human societies tend to protect their version of the human against subversive criticism: all have their mantraps. And the savagery of their reprisal on the victims is what we need to under- stand. Whence this excess of hatred for the helpless victim? It is there in the passion story and in the files of Amnesty: we apparently hate the victim for being victim. What might that say?

The fury of the torturer ends with the break-down of the victim, whether this break-down takes the form of raging anger or whimpering submission. It seems that the rage of the torturer is only evoked as long as the victim remains unbroken. In his/her non-retaliation in hatred the victim remains human, continues to offer a human relationship to the torturer. In making this offer, the victim is shown to be stronger than the torturer, more willing (in sheer helpless victimhood) to bear the cost of promoting a more human world. And it is this truth of the situation that arouses such fury. The victim, willing or unwilling representative of a truer humanity, though helpless, stands in judgment on our sell-out of humanity a sell-out due to our fear of the cost. The victim confronts us with the humanity we have suppressed within ourselves. It is an intolerable situation.

To have another in your power is to be in a position of shame as a human being. We both want this power and resent the shame. Of course, we must hate the victim for being victim, whether it be the poor person in our locality or the majority of our fellow human beings who are condemned to be losers in the competitive world of our making. (3)

On this reading, the more truly innocent the victim the greater the animosity that will be occasioned in us, since we are undergoing a more radical and intolerable condemnation. I find that I cannot imagine the soldiers treating Barabbas as they did Jesus. They have reason to hate this man who is willing to fight and kill them. But, now that he is in their power, he does not provoke the kind of hatred we see displayed toward Jesus. We assume that we hate people because of the harm they do or can do to us: it may be the case that we hate people much more because of the harm we do to them.

In the light of this, the choice of Barabbas over Jesus should not amaze us. It is entirely predictable. Barabbas is not a problem. He is, of course, dangerous, but we have the army, police, prisons. In all he says and does Barabbas justifies us to ourselves. He justifies Pilate in exercising the kind of power Pilate exercises: Pilate needs people like Barabbas to justify himself. Barabbas justifies the rest of us in his wanting basically the kind of thing we want. Barabbas would change the actors but not the basic power relationships of our world. Jesus, on the other hand, confronts us with the demands of the humanity we have long ago sacrificed on the altars of expediency. Of the two, Barabbas will elicit much less hostility from us. The weakness of God, mediated through a human sufferer, is more threatening to us than any human power.

The Gospel story also speaks of the role of the mob in the passion of Jesus. The mob is unthinking, easily manipulated. But its animosity must also be investigated. They probably had no idea of what Jesus was about; all that they could see was that he had run foul of the system. This was the self-same system that was oppressing them. Yet they shouted ‘Crucify him.’ Without understanding? Perhaps, to same extent. But, even if they had understood, they would still have done it. It is less terrifying to put up with the evil we know than to face the vulnerability of being simply human.

All of this says much about the nature of evil. The paradigm of sin which governs the Bible is ‘settling for the flesh-pots of Egypt.’ It is the refusal to move on towards true freedom. Within this model, it is easy to see how the greatest evil is perpetrated in our choice of the good. In our choice of what we will define as worthwhile, we set up what will be institutionalized, defended to the death. Our institutions, including our religious institutions, created to promote life, end up promoting death. Instead of openness to the summons contained in the presence of victims to judge differently and to go beyond what we have already instituted, we blame the victim for being victim.

John Taylor suggests that it is possible and necessary to probe deeper still into the sources of our hate and aggression. With whom, he asks, are we habitually angry in an inner rage which we fear to admit? Our anger is really directed against life itself and the Giver of life. Corresponding to those embodiments of historical fear and hate that we call military-industrial complexes are complexes of anger and hurt within, fed by our daily resentment at our wasted lives, our sense of helpless futility in the face of what life demands. The one we hate is the One responsible for making life like this: God.

We do not easily admit to hating God. This prevents us from being in touch with the source and extent of our hardness of heart, our inability to accept the human when we meet it. The concern of the Gospel revelation is to reconcile us to God, we who have never forgiven God for making us the vulnerable human beings we are.

So Jesus is not making excuses for us in this word from the cross. He is naming the unconscious movement of evil in us to put us in touch. Since he does it without condemnation, we are enabled to face the source, the self-crucifixion of life-in-us that leads to the crucifixion of others. (4)

To enter into the Gospel story of what happened to Jesus is to be led to identify in ourselves the evil which we see in others. Far from undermining our struggle against evil, this self-knowledge is what empowers creative struggle against evil. Creative struggle is grounded in solidarity and compassion, a compassion which understands that in oppressors which makes them such, a compassion grounded in self-knowledge.

That next step, I think, is possible if we allow ourselves to be moved by the truth of a Love which is so committed to creation that it is willing to suffer everything for the sake of creation, a Love which gives in such irrevocable fashion that for God there is no possibility of going back. We need to be so affected by this Love that we can stop resenting the human condition and the Giver of life. We may even come to cherish creation, including the vulnerable poverty of being human. We may even come to live from love/forgiveness and then we would no longer need to blame the victim for being victim.

NOTES:

1 – Your Word Is Near. New York: Newman Press, 1968, p. 131.

2 – London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1975.

3 – “I find myself acting violently toward people to make them afraid of me. This is my duty but I feel humiliated by my conduct.”

“It wears me down as a person. It breaks me.”

[Israeli soldiers in the West Bank. TIME, January, 1989]

4 – This insight underlies the work of Sebastian Moore, The Crucified is No Stranger. London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1977 and the more sweeping thesis of Rene Girard, “The Gospel Passion as Victim’s Story” in Cross Currents, Vol. XXXVI, No. 1, Spring 1986.

TUESDAY: The Mystery of Evil by Fr Brendan Lovett from his book, ‘It’s Not Over Yet – Christological Reflections on Holy Week’, published by Claretian Publications.

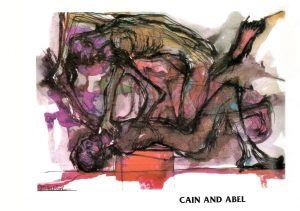

The drawing is by artist Roland Peter Litzenburger. One of a series of picture meditations before the Liturgy of the Cross on Good Friday.

No. 1 Fratricide: The Genesis story of the first murder is taken as appropriate beginning of a story that is not over yet.

Abel was a shepherd and Cain a tiller of the soil (Gen. 4-2)

The source of the conflict lies in different ways of life. We who try to gain our identity by our performance within a given way of life are most deeply threatened by such difference, by otherness. Today we consider it legitimate to place all life at risk of annihilation to further our preferred way of life. Instead of welcome for the other as the one in and through whom I may receive myself anew, we strive to control others and make them in our image, we reduce the other to being part of our world, hoping in this way to shore up our deeply uncertain and shaky identity. And so we gain our identity at the expense of the others.

The conflict is between family members. Since there is but one human family, all murder is sororicide and fratricide. If the others persist in trying to be true to themselves, the intolerance escalates to the point of ultimate violence. The earth, the universe itself, screams out at the outrage them perpetrated.6

![ITS NOT OVER YET – by Brendan Lovett[1256]_32_32-page-001](https://columbans.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ITS-NOT-OVER-YET-by-Brendan-Lovett1256_32_32-page-001.jpg)