Fr Alo Connaughton spoke to Fr Pat Egan about that fateful day in Chile’s history when the military, led by General Augusto Pinochet, seized power in a coup, overthrowing the Popular Unity government of President Salvador Allende.

Fr Pat Egan remembers Chile’s 9/11 well. The ‘Eleventh’ (El Once) can mean only one thing: the coup of 11th September 1973. Pat was there for years before and after the military takeover that brought the government of President Salvador Allende to a bloody end. This left-wing coalition had come to power in 1970 after a fair election. Although the parties won enough seats to form a government, they never had an overall majority.

Did Fr Pat see the coup coming? “A failed coup attempt in June and a state of political paralysis created a sense of dread; the government couldn’t function. Most weekdays some big group was on strike – today the teachers were out protesting against the government, tomorrow the students were on the streets against the teachers and supporting the government.

The day after it would be the truck drivers against the government and the day after, the factory workers… There were queues for all the basic necessities and runaway inflation. Although the atmosphere was tense, freedom of information wasn’t curbed, even if the views were extremely polarised.”

Was Allende’s government popular? “It was enthusiastically welcomed by over 36% of voters, and generally supported, at the beginning, by maybe half the people. It had many good plans. The nationalisation of the country’s copper mines, and tighter control of the banks was widely supported. Internally the coalition had irreconcilable tensions; mistakes were made.

But it had to deal with legal and illegal opposition, sabotage, market manipulation, hoarding of essentials and opposition from most of Chile’s wealthy elite and sections of the military. There were international boycotts. Covert actions of foreign multinationals and the CIA were subsequently well documented.

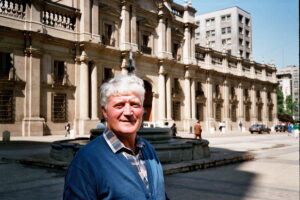

Columban missionary Fr Pat Egan outside La Moneda, the Presidential Palace in Santiago, Chile.

On the morning of Tuesday 11th September 1973, Fr Pat arrived early to the Columban city centre headquarters. It was only then he discovered a meticulously planned coup was in progress; radio announcements ordered people home. He walked two miles through back streets to get a lift home with some Irish Cross and Passion Sisters. Once back in the poorer western suburb of Lo Prado rumours began to filter in.

The presidential palace had been set on fire by Air Force rockets. Those who could listen to Radio Magellanes, the last free radio on air, heard, sometime after midday, an emotional farewell message from President Allende who saw what was coming. He was dead within hours.

The democratically elected President of Chile, Dr Salvador Allende. He headed a coalition of the Communist, Socialist, National Democratic and National Vanguard parties. He was ousted from power on 11th September 1973 by a military coup led by General Pinochet. Photo: Lynn Pelham/Camera Press.

Arrests began almost immediately – political and community leaders and trade union officials were the first. About six in Pat’s area were taken away never to be seen again; others were released after torture. Order of a sort was quickly restored but now fear was everywhere. In Pat’s first parish, the Port of San Antonia, dockworkers had gone to a meeting with the new military officials to discuss the protection of their rights.

Four of them were found dead the following day – terrorists shot while trying to escape the military said. The National Stadium in Santiago and the large indoor Estadio Chile were turned into detention centres – places of torture and death for many. A nightly curfew was imposed for years to come.

A miners march in Chile 1973. Photo: Alo Connaughton.

Back in the 1960s the Catholic Church had experienced a great revival after the Santiago General Mission and Synod. During Allende’s Unidad Popular government participation dropped a lot in the poorer areas, in part because of the huge increase in social and political activity at grassroots level; everyone was busy at weekends. People in poor neighbourhoods and the religious who worked with them were, in general, pro Unidad Popular.

Many of Chile’s bishops were sympathetic but with some reservations. The lines of communication between President Allende and Cardinal Silva remained open and on a few occasions Allende asked for his help. About three weeks before the coup Allende came secretly one evening to the Cardinal’s house to have dinner with him and Patricio Aylwin, leader of the opposition.

As they sat down for an after-dinner drink Allende joked, “This is Chile: the President of the Republic a mason and a Marxist, meets with the leader of the Opposition in the house of the Cardinal. This wouldn’t happen in any other country.”

The first Sunday after the coup, San Gabriel church in Lo Prado was packed as Fr Pat read a letter from Cardinal Raul Silva to all parishes. The Cardinal spoke of the immense pain he felt for the bloodshed and the tears of so many people. He wrote: “We ask for respect for those who have fallen in the struggle and in the first place for he who, until 11 September, was President of the Republic … Let there be no unnecessary reprisals. The sincere idealism which inspired many of those who are now defeated should be taken into account … It is a time to end the hatred and begin a time of reconciliation … We hope that the progress achieved by the previous governments with regard to workers and small farmers will not be put aside …”

Cardinal Silva did not limit himself to stirring words. Within days the ecumenical Committee for Peace (Comité pro Paz later to become the Vicaria de Solidaridad) was up and running. This offered legal aid, protection and often, places to hide, for those in danger of arrest, torture or death.

It grew to employ scores of lawyers, counsellors, social workers, medical personnel -and annually attended the needs of tens of thousands of people. All this was important under a new regime with little or no respect for basic rights.

After the coup the Church experienced another resurgence. The new rulers allowed little meaningful participation in the life of the country. This left many talented men and women without an opportunity to make a contribution to civil society.

Many of them began to participate in the Church, a lot as Mass-goers but also as participants in welfare activities, culture groups, awareness raising groups, liturgy, education and so on. All of these functioned under the umbrella of the Church and in spite of efforts to limit or control them.

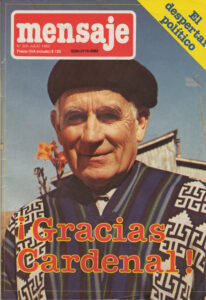

. A cover of Mensaje from July 1983. Published by the Jesuits, it was one of Chile’s most esteemed magazines. Columban Fr Alo Connaughton took this photo of Cardinal Raul Silva which was used to mark the Cardinal’s retirement.

Over the next 17 years some 3,200 people were killed by military agents, 1,200 of those are still among the disappeared. About 40,000 were imprisoned as political prisoners.

How did the return to democracy come about? Fr Pat underlines that with the passing of time and a lessening of repression the people’s courage began to return and with it, demands for a return of democracy. At the start there were small expressions of the will of the people – things like the beating of pots at a fixed time of night.

This led to street protests and strikes. In 1988, convinced he would win, Pinochet allowed a plebiscite – yes or no to a continuation of (disguised) military power. He lost but conceded. A new coalition government came into power in 1990 with Patricio Aylwin as president.

Looking back, was anything learnt from those years? Pat speaks of the 63% defeat in a plebiscite in 2022 of a new Constitution drafted by a heavily left-weighted Assembly. An election last May produced a drafting assembly now dominated by right wing candidates.

Acknowledging his defeat Chile’s young, radical President Gabriel Boric said in summary, “We squandered an opportunity because we did not listen to those who thought differently to us. We appeal to the winners not to make the same mistake.” A high price for some wisdom already freely available in the history books.

Fr Alo Connaughton is a former editor of the Far East magazine. He worked in Chile between 1975 and 1993 as a parish priest, in the education of young religious and in administration. He also served as regional director of the Columbans in Chile.

Read more on the Columbans and Chile under Pinochet in: ‘I Surrender: A Memoir of Chile’s Dictatorship’ by Kathy Osberger (Orbis Books 2023).