Eimear Crawford of St Louis Grammar School, Ballymena wrote the winning article in this year’s Columban Schools Media Competition on Fr Alec Reid, who was pivotal to the peace process in Northern Ireland.

William Scholes, Features Editor of the Irish News, described the article as: “Fluently written, thoroughly researched and inspired by the Beatitudes, this entry was a welcome assessment of Fr Alec Reid, a towering figure who was not only a true changemaker but also a peacemaker. It’s encouraging that a new generation is aware of his contribution to the peace process, and that they might be inspired by his example to build the peace in the future.”

Eimear Crawford explained, “I chose Fr Alec Reid because I think it’s so important to recognise the changemakers who have inspired peace and reconciliation within our own country. Fr Reid is especially inspirational to me because he was able to look past division and work for every life endangered by the Troubles.”

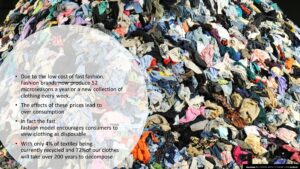

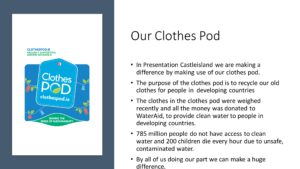

Blaithin McElligott of Presentation Secondary School Castleisland, Co Kerry won first prize in the images section. Her artwork, highlighted the cost of fast fashion and promoted her school’s clothes pod, was judged by William Scholes to have been an “informative entry” which “made an impact with its imaginative presentation and thoughtful examination of the issues around ‘fast fashion’ and the implications of the trend. That it ended on a positive note – the school’s Clothes Pod – shows that we can all make a real difference and be changemakers, wherever we are.”

Blaithin McElligott explained that in Presentation Castleisland “we are making a difference by donating clothes to our clothes pod which recycles old clothes and the money raised goes to the charity Water Aid. We are now also applying for our water flag. Thank you again for choosing my project.”

Winning Article

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God”- Matthew 5:9

Northern Ireland in the 21st century is a blessedly different place than it was in the century that preceded it. I think of my own childhood, devoid of the bomb and the bullet, and the shocking stories told by my relatives, growing up during the 70s and 80s, stories about shootings, burning cars and harassment.

The Good Friday Agreement heralded a new dawn for Northern Ireland, leading us towards the path of peace, bringing an end to the Troubles. There were many key people involved in the creation of the Agreement, but one figure that particularly stands out to me is Father Alec Reid, a Redemptorist priest from Clonard in Belfast.

Father Reid did not claim allegiance to any political party or ideology. Instead, he explained what motivated him, “I used to say that I don’t belong to any political party, but I represent the next person who is going to be killed in the troubles. The church has a moral obligation to get stuck in when people are suffering and to try and stop it.”

Not only was this a viewpoint that was all too rare during the bloody days of the Troubles, but it also exemplifies the teachings of the Catholic church: we are all part of one human family, regardless of our racial, ethnic, economic, or ideological differences.

Perhaps one of the most haunting images of the conflict depicts Father Reid, knelt over the body of a British soldier. In what became known as the corporal killings, two British soldiers who accidentally drove into a republican funeral were beaten and shot by the IRA. Father Reid was warned to stay away by the assailants, and even threatened with death, but courageously went to help the soldiers.

When nothing could be done for them, he performed the last rites. This simple act of human decency evokes another teaching of the Catholic church, everyone has a fundamental right to life, and we each have a responsibility to do what we can to uphold that.

What was not known at the time Father Reid’s picture was taken is that he was carrying with him a bloodstained envelope from Gerry Adams, to be given to John Hume, leader of the SDLP. Father Reid was instrumental in bringing Sinn Féin into the political dialogue, a process that would eventually culminate in the 1994 IRA ceasefire. These talks helped to change Sinn Féin’s policy, moving away from armed struggle against Britain towards a focus on self-determination and achieving their aims through non-violent, political means.

Following the success of the talks, Gerry Adams acknowledged that peace would not have been possible without the efforts of Father Reid, “there would not be a peace process at this time without [Father Reid’s] diligent doggedness and his refusal to give up.”

The negotiations set up by Father Reid paved the way for the Good Friday Agreement, and he acted as Sinn Féin’s contact person with the Irish government from 1987 to the signing of the Agreement in 1998.

The conversations between Hume and Adams were held secretly in rooms in Clonard Monastery. It was a fitting location for the negotiations to take place, the monastery had been a centre of peace-making and reconciliation and had strong links with the local Presbyterian church.

The Hume-Adams talks were not the only important discussions to take place at Clonard, other interfaith talks held at the monastery also played a vital role in brokering the 1994 ceasefire. Pope Paul IV taught “if you want peace, work for justice.” Father Reid worked for both, creating an atmosphere where people of all religions and beliefs could come together and try to build a better future.

Father Reid’s contribution to the peace process in Northern Ireland did not end with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. In 2005, he was one of the witnesses to the decommissioning of IRA weapons, a critical hurdle in the peace process. Everyone recognised how difficult the struggle for peace had been, and it was essential to preserve it, however fragile it was. 2 Corinthians 5:17 reads, “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, the new creation has come: the old has gone, the new is here.”

The bad old days of the Troubles had gone, but the new, peaceful creation birthed by the Agreement would have to be nurtured. Father Reid’s presence, along with Methodist minister Harold Good, was vital, as he was a trusted figure and a known peacemaker and helped to assuage the fears of those sceptical about the republicans’ intentions.

Father Reid was far from the only person involved in bringing peace to Northern Ireland. What stands out to me about him is that unlike some of the other architects of peace, he was wholly unmotivated by a desire for constitutional change or his own political beliefs. Instead, he simply valued the sanctity of human life, and wished to see an end to the atrocities that stole so many innocent lives.

Journalist Brian Rowan summed up the impact that Father Reid had on the Northern Ireland peace process in the BBC documentary, 14 Days, “I think when the journalists look back on the 30 years of conflict here, and on the journey of war to peace, the story will not be told without the name of Alec Reid right in the middle of it all.”

Making a Difference by Blaithin McElligott